Mast cell tumors are a common type of skin cancer in dogs. They range in severity from small, localized tumors that can remain stable for years to malignant cancers that can quickly spread throughout the body. A wide variety of treatment options are available to help manage canine mast cell tumors.

Key Takeaways

- A mast cell is a type of immune system cell. A mast cell tumor in a dog is cancer that occurs in mast cells.

- Life expectancy of a dog with a mast cell tumor depends on how aggressive the cancer is. Dogs with high grade mast cell tumors may only live 2-3 months, while dogs with low grade mast cell tumors can live 2-4 years or more.

- Mast cell tumors in dogs are not always fatal.

- How fast mast cell tumors spread in dogs depends on how aggressive the individual dog’s cancer is. Some are cured with surgery, while others can recur and spread throughout the body.

- The advanced stages of mast cell tumors in dogs can include ulcerated tumors, stomach ulcers, discomfort, and possibly anaphylaxis from massive histamine release.

- We don’t know what triggers mast cell tumors in dogs, but it is likely a combination of environmental and genetic factors.

What Are Mast Cell Tumors?

Mast cell tumors (MCTs) occur when mast cells—a white blood cell frequently found in connective tissue—become cancerous and proliferate abnormally.1,2 These cells contain several bioactive compounds, including histamine and heparin, which, in high concentrations, can lead to additional issues beyond the tumor itself.

While mast cell tumors can occur anywhere, they are most commonly found in the skin, subcutaneous fat layer, or within organs such as the spleen, liver, or kidneys.3,4

Stats and Facts About Mast Cell Tumors in Dogs

- MCTs are one of the most common cancers found in dogs, comprising around 20% of all skin tumors.5

- Approximately 50% of MCTs are malignant and prone to rapid growth and spread.4

- Other mast cell tumors grow more slowly and remain localized to one area for long periods.2

- It can be difficult to determine whether an MCT will remain localized or metastasize (spread) to other areas of the body, so all these tumors should be considered potentially malignant.

- Many veterinarians call MCT “the great pretender” because tumors can look like many other skin issues.

What Causes Mast Cell Tumors in Dogs?

No specific cause of mast cell tumors has been identified at this time. Likely, a combination of risk factors, including genetics and environmental exposures, contribute to the development of this cancer.

MCTs are one of the most common cancers found in dogs.

Risk Factors

While all dog breeds can develop MCTs, some breeds do appear to be more susceptible, including:

- Boxers

- Boston Terriers

- Bull Terriers

- Labrador Retrievers

Some dogs may have mutations in the c-KIT gene, making them more prone to developing mast cell tumors. Your veterinarian may want to screen your dog’s tumor for this mutation.20

These tumors may occur in dogs of any age but are most common in middle-aged and older individuals. No association between sex and reproductive status has been found.2,4,7

Dr. Demian Dressler breaks down the trickster cancer, mast cell tumors, in this episode of DOG CANCER ANSWERS.

Symptoms of Mast Cell Tumors

For mast cell tumors in the skin or subcutaneous fat, owners are often the first to identify an issue when they find a lump on their pet at home. Some of these masses may appear red or itchy due to the histamine content of the mast cells.8

Most MCTs are found on the body or the limbs, though they may occur anywhere, including at the nailbeds, around the rectum, and inside the mouth.7,9

MCTs can easily be mistaken for lipomas8—a benign fatty tumor—so it’s important to have your veterinarian check out any lumps or bumps you find on your pet.

Other symptoms you may notice often occur due to the histamine and heparin content of the mast cells and can include:7,10

- Decreased appetite

- Diarrhea

- Blood in the stool

- Clotting issues

- Delayed wound healing

Diagnosing Canine Mast Cell Tumors

MCTs in the skin and subcutaneous tissues can often be diagnosed with a fine needle aspirate and cytology. Your veterinarian will stick a needle into the mass to obtain a sample of the cells and then examine these under the microscope.4,10

Mast cell tumors inside organs can be more difficult to identify and may need additional testing such as radiographs and ultrasound.

Prognosis and Staging

Mast cell tumors are classified into three grades based on their histologic appearance,4 and the prognosis varies depending on their classification.

- Grade I tumors are well differentiated and result in the most extended survival times, with around 90% of dogs surviving more than four years.7

- Grade II tumors are the most common and may be more locally invasive. In one study, 47% of dogs with grade II tumors survived more than four years.7

- Grade III tumors carry the poorest prognosis, with only 6% of dogs surviving more than four years.7

Another 2-tier system, the Kiupel system, may better define some low-grade tumors’ biologic behavior.

Low-grade mast cell tumors (those with a low mitotic index) tend to have good long-term survival rates of greater than two years. However, high-grade mast cell tumors (those with a high mitotic index) tend to have a poor survival rate, with a median survival time of only two to three months if left untreated. Chemotherapy, radiation, and tyrosine kinase inhibitors can help those dogs live longer with good life quality.2

Further staging to determine if and to what extent a mast cell tumor has spread can help your veterinarian make the best recommendations for your pet. This may include testing such as radiographs, ultrasound, lymph node aspirates, and/or bone marrow aspirates.

Veterinary oncologist Brooke Britton breaks down the mitotic index and how it's used in treating cancer in this DOG CANCER ANSWERS episode.

Canine Mast Cell Tumors Treatment

Various treatment modalities are available to help manage canine mast cell tumors, including medical management, surgery, chemotherapy, radiation, and new evolving treatment strategies. Your veterinarian can help you decide which options make the most sense for your dog.

Medical Management

Over 80% of dogs with mast cell tumors show signs of ulcers in their stomach and intestines.7,10 Medical management helps minimize the impact of these ulcers and may include medications such as antihistamines (cimetidine, diphenhydramine, etc.), proton pump inhibitors (omeprazole, etc.), and coating agents (such as sucralfate).4,10

Degranulation Events

If a tumor is agitated, its cells may release large amounts of histamine in a degranulation event. This results in a large area of red, itchy skin around the tumor. Treating with antihistamines can prevent degranulation from occurring, causing the inflammation to subside and the tumors to appear smaller.

Antihistamines and proton pump inhibitors (such as omeprazole, brand name Prilosec®) are often recommended alongside prednisone in cases where surgical removal, chemotherapy, and/or radiation are not an option.

Using Tagamet and Benadryl with Mast Cell Tumors

You may have seen the Tagamet and Benadryl (cimetidine and diphenhydramine) “protocol” touted online. Both are histamine blockers, so using them to help with symptom relief may make sense. But do they “cure” mast cell tumors (or other cancers, as the proponents claim)? Currently, limited data is available on the effectiveness of this drug combination.

Omeprazole and esomeprazole (proton pump inhibitors, a different class of drugs) have shown some early evidence in the lab that they may have some ability to affect mast cell tumors directly.24 However, further research is necessary to determine if this is a viable option for treating mast cell tumors in dogs.

While there are likely some benefits from either of these drug combinations and minimal side effects, it should not be considered a “cure.”

Are Tagamet and Benadryl together the only thing your dog needs? No, and Dr. Nancy Reese explains why in this Dog Cancer Answers episode.

Surgery

Surgery is often the treatment of choice for localized cutaneous tumors that do not appear to have metastasized. Because some mast cell tumors can be locally invasive, your veterinarian will remove a wide margin of tissue around the tumor to decrease the likelihood of recurrence. Even with this precaution, 40% of tumors may come back.6

Your veterinarian may recommend combining surgery with other treatment modalities, such as chemotherapy, particularly in areas where it is hard to get wide margins, such as on the face or legs.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy may be recommended for tumors that cannot be entirely surgically removed or have already spread to other locations in the body. A variety of chemotherapy protocols have been shown to be effective against mast cell tumors including:2,10

- Prednisone

- Vinblastine

- Lomustine

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) such as masitinib and toceranib (Palladia)

Your veterinarian can help advise you about the most appropriate chemotherapy protocols for your pet’s situation and any potential side effects.

Vinblastine and Prednisone

Vinblastine/prednisone is a common chemotherapy protocol for mast cell tumors that cannot be surgically removed. This consists of a combination of oral prednisone along with intravenous injections of vinblastine, with many protocols calling for eight injections over twelve weeks.2

Lomustine

Lomustine is an oral treatment usually given every 2-3 weeks. Lomustine can cause significant bone marrow suppression and liver damage and must be monitored closely. Many dogs on lomustine therapy are prescribed a liver protectant to help minimize the drug’s effect on the liver.2

Masitinib and Palladia

Masitinib is utilized primarily in dogs with KIT mutations and has been shown to slow the progression of the disease and improve survival times.2 (Masitinib is not available in the U.S., but it is available in the E.U.)

Toceranib (Palladia) is also most effective in dogs with KIT mutations. However, the compound has also been shown to be effective in dogs without these mutations.2

Both of these TKIs are oral treatments that are generally well tolerated, though they can cause gastrointestinal side effects and, in rare cases, potentially severe protein loss through the kidneys.2

Electrochemotherapy

Another new treatment technique under investigation is electrochemotherapy, where electrical impulses help deliver chemotherapy into the target tissue. Early research shows this method may be as effective as surgical removal for smaller nodules.15

Radiation

Mast cell tumors are highly sensitive to radiation, and this therapy is often utilized for localized tumors either when a tumor cannot be removed, or complete excision has been unsuccessful.

In some instances, radiation treatment may be combined with other modalities,2,11 particularly for tumors that cannot be surgically removed.2 In one study, dogs with cutaneous mast cell tumors that could not be removed surgically were treated with radiation as well as toceranib and prednisone. Over 50% of the dogs showed a complete response to this protocol, and the average time of tumor stabilization was around one year.23

Immunotherapy

While some biological response modifiers or immunostimulants have been investigated in a research setting, results are mixed, and none are commercially available for use at this time.8,12,13

Vaccine

No vaccine targeting mast cell tumors is available at this time.4

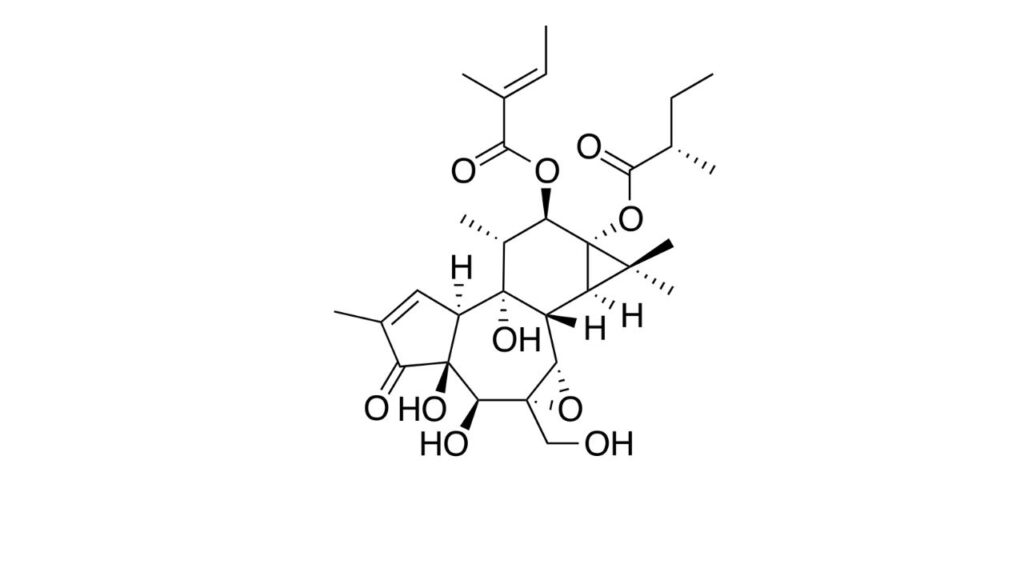

Stelfonta®

One of the newest treatment options for mast cell tumors is a compound called tigilanol tiglate (brand name Stelfonta) which has been approved for use on small cutaneous or subcutaneous mast cell tumors located on the legs which have not spread to other locations in the body. Stelfonta is injected directly into the mast cell tumor. It causes local necrosis and sloughing of the affected tissue; in other words, a wound that eventually heals. The response rates to Stelfonta are promising, however, many dogs experience significant side effects, including pain, lameness, low protein levels, and secondary infections.14

Diet

It is important to feed dogs with cancer a high-quality, balanced, and varied diet that meets all their energy and nutritional needs. Always discuss any diet changes with your veterinarian to determine the best plan for your pet.

Cancer cells’ preferred energy source is glucose.16 For this reason, some people opt to feed a low-carbohydrate diet to their dog after a cancer diagnosis.

Another option in dogs with mast cell tumors may be a low-histamine diet, which could help decrease any further intake of histamine through the food and decrease the ingestion of compounds that may interfere with the dog’s ability to break down histamine.17

When utilizing a low-carbohydrate, low-histamine, or any other type of homemade diet, working closely with a veterinary nutritionist is important to ensure you provide a complete and balanced diet for your dog.

To locate a veterinary nutritionist, refer to the American College of Veterinary Nutrition’s website. If there is no veterinary nutritionist in your immediate area, many can do remote consultations with you or your veterinarian.

Supplements

Research in a group of Labrador Retrievers found that dogs deficient in vitamin D3 may be at higher risk of developing mast cell tumors.18 Additionally, low magnesium levels have been shown to induce mast cells’ emergence in rats’ livers.19 Supplementation of these compounds and other nutritional or herbal supplements may be helpful in a treatment protocol for dogs with mast cell tumors.

That said, never give vitamin D or magnesium without consulting your veterinarian. Both of these supplements can lead to toxicity if too much is given.

Discuss all supplements with your veterinarian before giving them to your pet.

Integrative Therapies

Another technique under study is injecting a hypotonic solution into the tumor. This has been shown to decrease the size of small tumors as well as to help decrease the likelihood of tumor reoccurrence at surgery sites.4

What the End Looks Like for Dogs with Mast Cell Tumors

Since some mast cell tumors can have a high rate of recurrence or metastasis, they should all be treated with respect. Low-grade tumors tend to carry a good prognosis, but high-grade tumors have a much shorter survival time.

Dogs may succumb to problems with localized tumors such as ulceration or infection, paraneoplastic issues such as gastrointestinal ulcers or anaphylaxis due to massive histamine release, or the spread of the tumor to other organs, including the lungs and liver.

Prevention Strategies

There are no current prevention strategies to keep your dog from developing a mast cell tumor.

- Thompson JJ, Pearl DL, Yager JA, Best SJ, Coomber BL, Foster RA. Canine subcutaneous mast cell tumor: characterization and prognostic indices. Vet Pathol. 2011;48(1):156-168. doi:10.1177/0300985810387446

- Garrett LD. Canine mast cell tumors: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Vet Med (Auckl). 2014;5:49-58. Published 2014 Aug 12. doi:10.2147/VMRR.S41005

- London CA, Seguin B. Mast cell tumors in the dog. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2003;33(3):473-v. doi:10.1016/s0195-5616(03)00003-2

- Misdorp W. Mast cells and canine mast cell tumours. A review. Vet Q. 2004;26(4):156-169. doi:10.1080/01652176.2004.9695178

- Meuten DJ, Kiupel M. Mast Cell Tumors. In: Tumors in Domestic Animals. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2016:176-202.

- Michael O. Childress DVM. Take 5: Key points for managing cutaneous mast cell tumors in dogs. DVM 360. https://www.dvm360.com/view/take-5-key-points-managing-cutaneous-mast-cell-tumors-dogs. Published August 12, 2019. Accessed March 15, 2023.

- O’Keefe DA. Canine mast cell tumors. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1990;20(4):1105-1115. doi:10.1016/s0195-5616(90)50087-x

- Oldford SA, Marshall JS. Mast cells as targets for immunotherapy of solid tumors. Mol Immunol. 2015;63(1):113-124. doi:10.1016/j.molimm.2014.02.020

- Govier SM. Principles of treatment for mast cell tumors. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2003;18(2):103-106. doi:10.1053/svms.2003.36624

- Blackwood L, Murphy S, Buracco P, et al. European consensus document on mast cell tumours in dogs and cats. Vet Comp Oncol. 2012;10(3):e1-e29. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5829.2012.00341.x

- Poirier VJ, Adams WM, Forrest LJ, Green EM, Dubielzig RR, Vail DM. Radiation therapy for incompletely excised grade II canine mast cell tumors. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2006;42(6):430-434. doi:10.5326/0420430

- Henry CJ, Downing S, Rosenthal RC, et al. Evaluation of a novel immunomodulator composed of human chorionic gonadotropin and bacillus Calmette-Guerin for treatment of canine mast cell tumors in clinically affected dogs. Am J Vet Res. 2007;68(11):1246-1251. doi:10.2460/ajvr.68.11.1246

- Lichterman JN, Reddy SM. Mast Cells: A New Frontier for Cancer Immunotherapy. Cells. 2021;10(6):1270. Published 2021 May 21. doi:10.3390/cells10061270

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first intratumoral injection to treat non-metastatic mast cell tumors in dogs. Nov 16,2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-intratumoral-injection-treat-non-metastatic-mast-cell-tumors-dogs

- Lowe R, Gavazza A, Impellizeri JA, Soden DM, Lubas G. The treatment of canine mast cell tumours with electrochemotherapy with or without surgical excision. Vet Comp Oncol. 2017;15(3):775-784. doi:10.1111/vco.12217

- Ho VW, Leung K, Hsu A, et al. A low carbohydrate, high protein diet slows tumor growth and prevents cancer initiation. Cancer Res. 2011, 71(13): 4484-4493. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3973

- Sánchez-Pérez S, Comas-Basté O, Veciana-Nogués MT, Latorre-Moratalla ML, Vidal-Carou MC. Low-Histamine Diets: Is the Exclusion of Foods Justified by Their Histamine Content? Nutrients. 2021;13(5):1395. Published 2021 Apr 21. doi:10.3390/nu13051395

- Wakshlag JJ, Rassnick KM, Malone EK, et al. Cross-sectional study to investigate the association between vitamin D status and cutaneous mast cell tumours in Labrador retrievers. Br J Nutr. 2011;106 Suppl 1:S60-S63. doi:10.1017/S000711451100211X

- Takemoto S, Yamamoto A, Tomonaga S, Funaba M, Matsui T. Magnesium deficiency induces the emergence of mast cells in the liver of rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo). 2013;59(6):560-563. doi:10.3177/jnsv.59.560

- Michigan State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. Detecting mutations in the gene c-Kit in certain types of tumors. https://cvm.msu.edu/vdl/laboratory-sections/anatomic-surgical-pathology/biopsy-service/detecting-c-kit-mutations

- Patnaik AK, Ehler WJ, MacEwen EG. Canine cutaneous mast cell tumor: morphologic grading and survival time in 83 dogs. Vet Pathol. 1984;21(5):469-474. doi:10.1177/030098588402100503

- Sabattini S, Scarpa F, Berlato D, Bettini G. Histologic grading of canine mast cell tumor: is 2 better than 3? Vet Pathol. 2015;52(1):70-73. doi:10.1177/0300985814521638

- Carlsten KS, London CA, Haney S, Burnett R, Avery AC, Thamm DH. Multicenter prospective trial of hypofractionated radiation treatment, toceranib, and prednisone for measurable canine mast cell tumors. J Vet Intern Med. 2012;26(1):135-141. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2011.00851.x

- Gould EN, Szule JA, Wilson-Robles H, et al. Esomeprazole induces structural changes and apoptosis and alters function of in vitro canine neoplastic mast cells. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2023; 256. doi: 10.1016/j.vetimm.2022.110539

Prilosec® is a registered trademark of AstraZeneca

Stelfonta® is a registered trademark of QBiotics Group Limited

Topics

Did You Find This Helpful? Share It with Your Pack!

Use the buttons to share what you learned on social media, download a PDF, print this out, or email it to your veterinarian.