Melanoma in dogs can be an aggressive cancer, but good outcomes are possible if it is caught early. There are several treatments available with many studies currently underway to find even more.

Key Takeaways

- How long a dog can live with melanoma depends on the location of the tumor. Aggressive tumors in the mouth or near mucous membranes may only have a survival time of a few weeks, while dogs with other forms of melanoma can live a year or more.

- The symptoms of melanoma in dogs depend on where the tumor is located. You may see a mass (dark or light in color), or notice drooling, trouble eating, lameness, licking at paws, nails falling off, or a poor appetite.

- Melanoma in dogs in usually treated with surgery followed by the immunotherapy vaccine Oncept, but other therapies are available as well. Starting treatment early gives the best chance of success.

- Dog melanoma can be painful depending on where it is located. Mouth and nail bed tumors tend to be the most uncomfortable, but ulcerated masses anywhere on the body can cause discomfort.

- It is difficult to get a complete “cure” for dog melanoma. Earlier, low-stage cases generally respond to treatment better than more advanced cases.

- Melanoma tends to spread quickly in dogs. For nail bed melanoma, 30-40% of cases have already spread by the time it is diagnosed. Many veterinarians assume that it has already spread in oral melanoma, as 80% of cases will metastasize. Other forms, such as eye and skin melanoma, are less likely to spread.

- Melanoma typically becomes fatal when the dog can no longer breathe normally or cannot eat (or is losing weight despite eating well). Aggressive forms can progress in a matter of weeks, while less aggressive forms may not cause an issue for over a year, especially with treatment.

Melanoma in Dogs: A Tumor of the Cells That Control Pigment

Melanoma is a tumor of the melanocytes or pigmented cells of the skin or mucous membranes. These cells can be found anywhere skin or mucous membranes are, so several types of melanoma exist.

Location Matters in Canine Melanoma

Melanomas generally tend to grow quickly and spread or metastasize to other locations in the body.

The location of a canine melanoma tumor tends to impact how aggressive it will be.1

For example, a general rule in melanoma is that if a tumor grows on or within one centimeter of a mucous membrane, it will behave dangerously.2 The lining of the mouth and nose are examples of mucous membranes.

Let’s discuss the main locations and types of melanoma in dogs.

Oral Melanoma (Melanoma in a Dog’s Mouth)

Melanomas that grow in the mouth are the most common and most aggressive variant of melanoma in dogs.

Oral melanomas account for 80% of melanomas,4 and are also the most frequently diagnosed malignant tumor in dogs.6

Oral melanomas are significant enough to warrant their own article here on DogCancer.com.

Nail Bed Melanoma in Dogs

The base of the nail is the second most common location for malignant melanomas in dogs.

Nail bed melanoma accounts for approximately 15-20% of melanoma cases4 and about 12% of all tumors on the toes.10 Forelimbs may be slightly more likely to be affected than hind limbs.

Nail bed melanomas can be very painful because they destroy the underlying bone.2 Often, these tumors look like a nail infection. They may even respond to treatments given for infection (usually antibiotics and anti-inflammatories) at first.2

Nail bed melanomas tend to metastasize at rates upwards of 50%.10 Amputation of the toe is technically curative if the tumor cells have not spread. However, an estimated 30% to 40% have already metastasized by the time they are diagnosed.2

The median survival time for nail bed melanoma is one year.2

Canine Melanoma in Mucocutaneous Junctions

Mucocutaneous junctions are where the mucous membrane meets the skin. This includes tumors that grow on the vulva, anal area, and lips (although these possibly count as “oral”).

These tumors are less common but also very aggressive. One study found that although anal sac melanomas are uncommon, they have a short survival time, with only 1 of 11 dogs alive after a year of treatment.7

Ocular or Dog Eye Melanoma

Nearly any part of the eye can grow a melanoma, but the iris or epibulbar (on the surface of the eyeball) regions are the most common.

Iris Dog Eye Melanoma

Iris melanoma occurs in the colored part of the eye. These tumors can be hard to see until they are really big.2

Iris melanomas are benign in 80% of dogs. Still, even benign melanomas can be problematic because they grow quite large and cause pain, inflammation, glaucoma (increased pressure in the eye), and vision problems.

(It is interesting to note that eye melanoma in cats is more malignant, with 60% to 70% of iris melanomas being malignant.)2

Enucleation, or surgical removal of the entire eye, is usually recommended for iris melanomas, whether benign or malignant. Smaller benign tumors may respond to laser therapy.2

Epibulbar Dog Eye Melanoma

Epibulbar melanoma occurs on the outer eye portion, where the white sclera meets the clear cornea. Melanomas in these locations are much less aggressive.

Smaller tumors may not need treatment, though larger tumors should be removed by surgery, laser, or cryosurgery.2 They are not expected to metastasize.3

Dermal, Cutaneous, or Skin Melanoma in Dogs

These melanoma tumors grow on skin with hair. Unlike in people, dog melanomas on the skin tend to be benign.

These benign tumors are sometimes called melanocytomas.3 Dermal melanomas make up approximately 5% to 7% of all skin tumors15 and are more common in dark-haired dogs. They often look like either solitary, dark masses or are flat and wrinkly, but can also lack pigmentation altogether.15

As mentioned, dermal melanomas are rarely malignant, but they are aggressive when they are.

- Skin melanomas are especially suspicious if located within a centimeter of a mucous membrane.5

- Approximately 12% of dermal melanomas are malignant6, so it is important to biopsy them or surgically remove them and send to the lab for identification.

- Alternatively, your veterinarian can try to get a cytology using fine needle aspirate, but dermal melanomas don’t usually exfoliate (let go of their cells) very well.

If your dog’s dermal melanoma does prove to be malignant, it is treated like the other types of malignant melanoma.

Non-malignant Melanomas, AKA Melanocytomas

Although benign melanomas (technically called melanocytomas) are much less common than malignant melanomas, they do exist.

Melanocytomas often grow in haired areas and arise from the external root of a hair follicle. They are more common on the eyelid.5 Melanocytic nevus are also very similar and appear as small, round, firm, dark masses (like a mole).5

As these tumors are benign and not likely to spread or cause harm over time, they are usually not treated unless they are in a position that causes discomfort or mobility problems. Your veterinarian may want to keep monitoring them over time.

Stats and Facts About Canine Melanoma

- Melanoma accounts for approximately 7% of all malignant tumors in dogs.9

- 80% of melanoma cases occur in the mouth.4

- 15-20% of melanoma cases occur in the nail bed.4

- Melanoma in the eye is usually benign.2

In some ways, melanoma in dogs is similar to that in humans, so research and treatments for one species will help the other.8

One notable difference is that malignant melanoma is associated with sun damage and exposure in humans, but the same association is not proven in dogs.2

What Causes Malignant Melanoma in Dogs

An exact and specific cause of melanoma is not known. As with many cancers, it is likely caused by many genetic and environmental factors happening at the same time.4

Dr. Brooke Britton explains why catching melanoma early gets the best outcome in this DOG CANCER ANSWER episode.

Risk Factors for Dog Melanoma

Much is unknown about what causes melanoma in dogs or what risk factors may be associated with it. The following are possible risk factors, but with no strong data to support them:

- Excessive licking one place on the skin causes a mutation in the cells.4

- Chemicals in the environment, hormones, or viruses.5

- Other sources of chronic inflammation, such as deep infections or burns.6

In general, neither sex is more likely to have melanoma.

Any breed of dog can get melanoma, but some breeds are overrepresented. Breeds that are diagnosed with melanoma more commonly include:1,4,5

- Airedale Terriers

- Bull Terriers

- Chesapeake Bay Retrievers

- Chihuahuas

- Chow Chows

- Cocker Spaniels

- Doberman Pinschers

- Golden Retrievers

- Irish Setters

- Poodles

- Schnauzers

Dark-haired dogs are more likely to have dermal or nail bed melanoma.2

One study suggested that Vizslas between 5 and 11 years old are more prone to benign melanocytomas,5 hopeful news for Vizsla owners.

Another study suggested that ocular (eye) melanoma, which is also usually benign, is possibly more common in female German Shepherds between 5 and 6 years old.5

Symptoms of Dog Melanoma

The symptoms of melanoma depend on where the tumor is located, whether the cancer has spread, and how severe it is. 4

Oral Melanoma Symptoms

Symptoms of oral melanoma often look similar to a variety of dental issues:4

- Bad breath

- Abnormal chewing habits

- Refusing to eat

- Drooling

- The presence of an obvious mass on the mucous membrane

Skin Melanoma Symptoms

Dermal melanoma symptoms include:1,4

- A visible tumor can vary in appearance, but dark, raised, or flat skin patches are common.

- Bleeding or ulcerated mass

- Occasionally, the melanoma will lack pigment (called amelanotic melanoma) and is pink in color. The fact that melanoma is amelanotic does not change anything about the treatment or prognosis recommendations.

Nail Bed Melanoma Symptoms

Aggressive nail bed melanomas are uncomfortable and can show a variety of signs:5

- Limping

- Licking toes

- Swollen toes

- Discolored nails

- Loose nails

Eye Melanoma Symptoms

Ocular melanoma is usually noticed as a dark mass in the eye or on the eyelid, a dark spot on the iris, swelling in or near the eye, or the eye is red or cloudy.5

Symptoms that Canine Melanoma Has Spread

If the melanoma has spread, symptoms of metastasis you might see in your dog include:4

- Losing weight

- Coughing

- Difficulty breathing

Getting a Diagnosis of Canine Melanoma

Diagnosis of melanoma starts with a physical exam by a veterinarian.4

The veterinarian is looking for just about anything abnormal on the skin and mucous membranes: dark patches, dark lumps, bleeding spots, small blisters, spots that won’t heal, or sometimes a rash on the belly, feet, or face.5

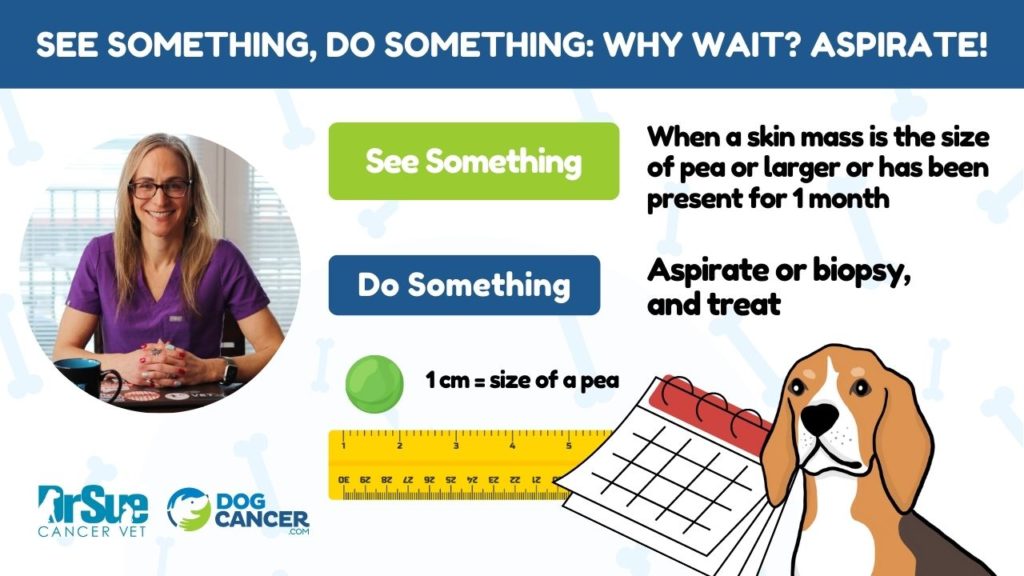

Fine Needle Aspirate: Possible Diagnostic Tool for Canine Melanoma

If your veterinarian finds something, or if you point out a problem area, your veterinarian will likely get a sample of the mass, called a fine needle aspirate.

This is when the veterinarian uses a needle and syringe to get a few cells out of the mass, then smears it across a slide for examination under a microscope (also known as cytology). Your veterinarian may recommend sending the slide for a pathologist to review it and use special stains that make cells easier to identify.

Some lumps and bumps aren’t likely to aspirate well because they are too hard or solid to get a good sample. Your veterinarian may want to skip the fine needle aspirate in these cases.

Biopsy: A More Likely Diagnostic Tool for Canine Melanoma

Suppose there is a complication with an aspiration sample, or your vet discovers it is “non-diagnostic,” meaning they couldn’t get a good sample.

In that case, they will likely recommend skipping straight to biopsy: removing the mass surgically and sending it to the laboratory for identification.

What the Vets Are Looking for That Indicates Melanoma

Several things on the cytology or biopsy can help a veterinarian or pathologist diagnose melanomas and predict how aggressively they may behave.

Ki-67

Several studies have found Ki-67 to be the most reliable indicator of how aggressive a dog’s melanoma will be.16

Ki-67 is a nuclear protein associated with rapid tumor growth and cell proliferation. Knowing if these proteins are present may help predict aggressive behavior.5 The pathologist can see these proteins with the help of a special stain.

A Ki-67 index greater than 15% suggests a bad prognosis.16

Nuclear Atypia

This is when the nuclei of the cells have an abnormal appearance associated with malignancy.16 Sometimes it is reported as “mild,” “moderate,” or “severe.”

Mitotic Index

Many studies suggest the mitotic index is the most accurate way to predict aggressive behavior in a tumor.

The pathologist looks for cells that are right in the middle of dividing, then counts how many there are in a high-powered microscopic field.2

The sample is then given a score.

In general, a tumor with less than three mitotic figures in a high-power field will likely express benign behavior and be less aggressive.2

Dr. Nancy Reese explains the mitotic index on DOG CANCER ANSWERS.

Additional Tests for Melanoma in Dogs

There might be other tests the veterinarian may want to run when chasing down a diagnosis. For example, because surgery is the first treatment in melanoma in dogs, your dog’s general health will need to be understood before he or she has anesthesia.

Generally, your veterinarian may recommend blood tests, urinalysis, or imaging procedures like X-rays, ultrasound, MRI, or CT.

If the melanoma is on the toe, they may recommend X-rays of that paw, and if the melanoma is in the eye, they may recommend more specific eye tests (such as tonometry to check eye pressure, Schirmer tear test, or a slit lamp exam).

Staging and Prognosis for Melanoma in Dogs

Staging means determining how much cancer is in the body and where it is located.

We want to know how big the tumor is and if it has spread (usually to lymph nodes or lungs). The tests listed above help your veterinarian determine what you and your dog are facing.

Large Melanomas in Dogs Might Not Need Many Staging Tests

If the melanoma tumor is already very large at diagnosis, it has likely already spread. Larger melanoma tumors are also more likely to be aggressive and are harder to remove surgically.1

In these cases, and especially if finances are an issue, staging may not be the place to spend money. Since the prognosis is almost certainly bad, it’s reasonable to skip staging tests and focus on seeking palliative (trying to help, not cure), and supportive care.

Small and Medium Canine Melanoma Tumors May Benefit from More Staging

Prognosis is highly variable for small or medium tumors, so finding out more information upfront will help you and your veterinarian make decisions.

It’s recommended to do at least basic cytology (to evaluate how aggressive the tumor is) and basic imaging (to determine if it has spread).

If the tumor has already spread to the lungs and/or lymph nodes or is aggressive, it carries a worse prognosis. Knowing this upfront really helps with treatment decisions.

Staging Melanoma

Staging is straightforward for oral melanoma (see separate article) but can be less clear in other melanoma sites. In general, for canine melanoma:

- Stage 1. The tumor is less than 1 centimeter in size and has not spread. With surgery alone, the median survival time is 15 to 18 months.1

- Stage 2. The tumor is 2 to 4 centimeters in size. With surgery alone, the median survival time is six months.1

- Stage 3. The tumor is over 4 centimeters or has spread to lymph nodes. With surgery alone, the median survival time is 3 to 4 months.1

- Stage 4. The tumor has spread to the lungs. Surgery is usually not even attempted in these cases unless partial removal will help with palliative care to improve the dog’s quality of life. Median survival time is 1 to 2 months,1 but may be only a couple weeks.

Once you have a diagnosis and know your dog’s melanoma’s approximate stage and prognosis, your veterinarian can guide you through the different treatment options.

Treatment for Canine Melanoma

Cancer treatment in dogs, in general, is not usually about getting a “cure.” Instead, the focus is on improving and maintaining the quality of life while hopefully extending the dog’s life beyond what would happen if the cancer wasn’t treated.

The goals of treatment for malignant melanoma in dogs specifically are:

- To control the local tumor.

- To stop it from spreading.

- To control any spread that has already occurred.

Traditionally, this has meant surgery and radiation, which are still the mainstays of treatment for melanoma in dogs.

However, a newer and very effective vaccine option can be used alone or be added to traditional treatment.

In general, chemotherapy has not been effective, but some new studies show promising results.2

Recurrence of melanoma is common, so multiple rounds of treatments are often required.5

Let’s look at each of these treatments in a little more detail.

Surgery for Canine Melanoma

Surgery is nearly always recommended to remove the primary tumor, regardless of location.2

The median survival time for surgery alone is approximately nine months, but this highly depends on tumor location, size, and if it has spread.5

- If the surgeon gets clean margins, meaning the surgeon got all the tumor, then possibly only the vaccine is next recommended.2

- Radiation and the vaccine are usually recommended if the surgeon did not get clean margins and some cancer cells were left.2

- The entire toe is usually amputated for nail bed melanoma, as the tumor has often spread to nearby bone. Most dogs have no trouble adjusting to a missing toe, especially one causing pain and lameness.

Surgical removal of lymph nodes is also often recommended if the melanoma has spread already. By the time it is diagnosed, 30% to 40% of melanomas have already spread.5

Chemotherapy for Dog Melanoma

The use of chemotherapy to treat melanoma is highly variable. It does not work well in human melanoma treatment, but some veterinary oncologists will add chemotherapy to other treatments if the tumor has already spread.2

One of the more common chemotherapy protocols is a dose of carboplatin every three weeks for a total of 4 to 6 doses.4

Some recent studies are again looking at some chemotherapy protocols that could benefit melanoma treatment. One study showed that carboplatin and piroxicam, given to Stage 4 patients, extended median survival time from 30 to 119 days.2

So far, one case study has found that Palladia (a chemotherapy commonly used to treat mast cell tumors) may also be effective for melanoma.17 This requires further investigation to determine whether this is a reliable treatment option.

Radiation for Melanoma in Dogs

Melanomas are relatively sensitive to radiation, so using this method can reduce recurrence or regrowth of the tumor.

Radiation is often started about two weeks after surgery removes the primary tumor. It treats areas where the surgical margins were not clean, and cancer cells were left behind.4

Large doses of radiation at less frequent intervals tend to work best,5 allowing the surrounding tissue to heal between treatments.

- A typical radiation protocol is one weekly treatment for 3 to 6 weeks.5

- Palliative radiation protocols intended to help the dog feel better may be less frequent or have varying doses.

Radiation is also beneficial to treat locations where surgery is impossible, such as in bones, teeth, jaws, tongues, and lymph nodes.5

If only radiation is used, the median survival time is nine months,5 but it varies depending on tumor size, location, et cetera.

One study with a rare nasal melanoma (in which surgery was not an option) reported a median survival time of several months with radiation alone, which was a good outcome under the circumstances.12

The side effects of radiation are usually mild and self-limiting and only affect the irradiated area. Symptoms include hair loss, changes in skin color, skin dryness, and skin irritation.9

Immunotherapy for Melanoma in Dogs: The Dog Melanoma Vaccine

For about the last decade, we have had access to a melanoma vaccine called Oncept® manufactured by Merial.13

Traditional vaccines are designed to train the body to recognize a disease before it happens, but immunotherapy vaccines are a little different.

Oncept is not used to prevent melanoma. The Oncept vaccine is used as a treatment after melanoma has been diagnosed.4

The Oncept melanoma vaccine for dogs works by alerting the dog’s immune system to the problematic melanoma cells. Melanoma tumor cells have a protein called tyrosinase, which helps it make melanin.13 The vaccine “alerts” the dog’s immune system to this protein, inciting the dog’s immune system to attack the melanoma tumor cells.

Oncept is usually given as one injection every two weeks for a total of four doses. Then, a booster is usually given every six months.1

Oncept is generally available through veterinary oncologists.

The vaccine works best in the following situations:2,13

- Oral or nail bed melanoma

- Stage 2 or 3 melanoma that has not yet spread to local lymph nodes

- Stage 2 or 3 melanoma, where the local lymph node has been removed

This vaccine appears to be very effective and offers a lot of hope to dogs with melanoma.

- Many dogs survive over a year with the vaccine.2

- A recent study showed that 75% of dogs in Stage 2 or 3 who had the primary tumor surgically removed and then received the vaccine lived over 15 months.1 Without the vaccine, the mean survival time was 3 to 6 months.

The melanoma vaccine is well tolerated, with minimal side effects.4 Some dogs will get a mild fever or pain at the site of the injection.13

The Oncept vaccine costs about $1,000 to $1,500 per dose, but this will vary depending on where you live.4

Dr. Demian Dressler explains the Oncept vaccine and why it can be used in any melanoma case in this DOG CANCER ANSWERS episode.

Diet for Dogs with Melanoma

The most important thing when feeding a dog with melanoma is to ensure that her diet is complete and balanced, providing all the nutrients her body requires. There are no specific dietary recommendations aimed solely at dogs with melanoma, though dogs with oral melanoma may need a soft or canned diet to make eating less painful.

Supplements for Melanoma in Dogs

There are no specific supplements targeting canine melanoma patients, but supplements used in cancer and for general immune support may be beneficial.

Integrative Therapies for Melanoma

Many novel treatments are being studied to treat malignant melanoma. Immunotherapy treatments in particular, seem to hold some promise due to melanoma’s close association with the immune system.6

In Brazil and Argentina, they are working on electrochemotherapy studies, which seem both fascinating and promising. With this technique, researchers inject a chemical into the tumor and then electrocute it lightly.9

While not specific to treating melanoma, massage, acupuncture, and touch therapies may be useful to help control pain and maintain quality of life.

Follow-Up After Treatment for Canine Melanoma

Regardless of how you address your dog’s melanoma, you must follow up with your veterinarian and oncologist. Oncologists typically recommend scheduling rechecks every three months for tumors that appear well-controlled by treatment and have not spread.1

At these visits, you should expect a physical exam to check the previous tumor site and lymph nodes, plus chest x-rays to check for spread.

If your dog gets Oncept, the vaccine needs a booster, typically every six months.

Palliative Therapy for Dogs with Melanoma

Palliative therapy is commonly recommended for dogs with advanced melanoma cancer and melanoma that has metastasized. It may also be recommended if your dog has other life-limiting conditions that make cancer treatments more difficult or impossible.11

With palliative therapy, the priorities switch from treating cancer to increasing life quality. Pain management and life quality will be the focus. You and your veterinarian will keep your dog comfortable and aim to maintain and increase his or her quality of life.

You will work with your veterinarian to determine the best follow-up schedule to ensure your dog is comfortable and living the best life she can, even with this diagnosis.

What the End Stages of Melanoma in Dogs Look Like

Melanoma is aggressive and metastasizes quickly, which is why death is often by euthanasia. A peaceful, pain-free, and fear-free death is the best option in the following scenarios:

- When your dog can no longer eat comfortably (usually, this is oral melanoma).

- When the tumor has spread to the lungs, your dog cannot breathe.

- When the tumor spreads to internal organs and affects the function of the gastrointestinal tract, it causes him to lose weight or refuse to eat.

- When your dog is feeling pain from primary or metastatic tumors.

If you start to wonder if it is time for hospice or to say goodbye or need help knowing when to schedule the day for humane euthanasia, speak to your veterinarian to get a compassionate and realistic understanding of your dog’s overall health and likely course of symptoms.

Prevention Strategies for Melanoma in Dogs

Because we don’t have a specific cause, there is no known prevention for melanoma in dogs.4 As with all cancer prevention, keeping your dog healthy in general with a healthy diet, regular exercise, and regular veterinary checkups is recommended. Your dog should have an exam by your veterinarian at least once a year.

Early detection of melanoma brings the best prognosis. Pay attention to your dog’s skin, and have any masses or lesions checked. A monthly nose-to-tail home exam will help you with this.

If you have a young dog, consider getting them pet health insurance. Pet insurance won’t prevent melanoma, but if your dog is unlucky enough to get cancer, the insurance policy will help you get him the treatment he needs.

- Rau, S. (2022) What is canine melanoma?, Metropolitan Veterinary Associates. Metropolitan Veterinary Associates. Available at: https://metro-vet.com/what-is-canine-melanoma/ (Accessed: December 4, 2022).

- Brooks, W. (2009) Malignant melanoma in dogs and cats, VIN. VIN: Veterinary Information Network. Available at: https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4952854 (Accessed: December 4, 2022).

- Medical oncology: 5 types of skin cancer in dogs (no date) Veterinary Hospital. NC State Veterinary Hospital. Available at: https://hospital.cvm.ncsu.edu/services/small-animals/cancer-oncology/oncology/5-types-of-skin-cancer-in-dogs/ (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

- Crnec, I. (2022) A pet owners guide to melanoma in dogs: Causes, symptoms, and treatment, Veterinarians.org. Available at: https://www.veterinarians.org/melanoma-in-dogs/ (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

- Melanoma (no date) Pet Cancer Society. ImpriMed, Inc. Available at: https://petcancersociety.com/types-of-cancer/melanoma/ (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

- Gonçalves, J.P. et al. (2022) Immunology of canine melanoma, IntechOpen. IntechOpen. Available at: https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/84589 (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

- Vinayak, A. et al. (2017) “Malignant anal sac melanoma in dogs: Eleven cases (2000 to 2015),” Journal of Small Animal Practice, 58(4), pp. 231–237. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/jsap.12637.

- Tarone, L. et al. (2022) Canine melanoma immunology and immunotherapy: Relevance of Translational Research, Frontiers. Frontiers. Available at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fvets.2022.803093/full (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

- Fonseca-Alves, C.E. et al. (2021) “Current status of canine melanoma diagnosis and therapy: Report from a colloquium on canine melanoma organized by Abrovet (Brazilian Association of Veterinary Oncology),” Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 8. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2021.707025.

- Wobeser BK, Kidney BA, Powers BE, et al. Diagnoses and clinical outcomes associated with surgically amputated canine digits submitted to multiple veterinary diagnostic laboratories. Veterinary Pathology. 2007;44(3):355-361. doi:10.1354/vp.44-3-355

- Mingus, L. (2021) Pet cancer treatment options: Radiation, Flint Animal Cancer Center. Available at: https://www.csuanimalcancercenter.org/2019/09/01/pet-cancer-treatment-options-radiation/ (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

- Davies, O. et al. (2017) “Intranasal melanoma treated with radiation therapy in three dogs,” Veterinary Quarterly, 37(1), pp. 274–281. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/01652176.2017.1387828.

- Canine Melanoma Vaccine, Oncept (2017) Petcancervaccine.com. Merial. Available at: https://www.petcancervaccine.com/ (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

- Homepage – Argus Institute: Counseling and support for pet owners (2022) Argus Institute. Colorado State University. Available at: https://vetmedbiosci.colostate.edu/argus/ (Accessed: December 6, 2022).

- Skin melanoma – canine. Veterinary Society of Surgical Oncology. https://vsso.org/skin-melanoma-canine. Accessed March 3, 2023.

- Smedley RC, Sebastian K, Kiupel M. Diagnosis and prognosis of canine melanocytic neoplasms. Veterinary Sciences. 2022;9(4):175. doi:10.3390/vetsci9040175

- Tani H, Miyamoto R, Noguchi S, et al. A canine case of malignant melanoma carrying a kit c.1725_1733del mutation treated with toceranib: A case report and in vitro analysis. BMC Veterinary Research. 2021;17(1). doi:10.1186/s12917-021-02864-3

Oncept® is a registered trademark owned by Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health USA, Inc

Topics

Did You Find This Helpful? Share It with Your Pack!

Use the buttons to share what you learned on social media, download a PDF, print this out, or email it to your veterinarian.