Dog anesthesia is a powerful tool that allows us to perform diagnostic procedures and treatments that would otherwise be impossible.

Key Takeaways

- Common side effects of anesthesia in dogs include stiffness, nausea, and grogginess.

- How long it takes a dog to recover from anesthesia depends on the dog’s overall health, how long the dog was under, and what procedure(s) were performed. Most dogs are back to themselves within 24 hours.

- You can help your dog recover from anesthesia by giving them a quiet place to rest, providing small meals, and giving any medications prescribed by your veterinarian.

- You can give your dog small amounts of water after anesthesia, just don’t let him gulp a bunch down at once.

- Dogs are “weird” after anesthesia because the medications interfere with how their nerves normally communicate with the brain. It can take several hours for all of the medications to be completely cleared from your dog’s system.

Three Kinds of Anesthesia Used in Dogs

There are many ways to classify dog anesthesia, but general anesthesia, sedation, and local anesthesia are three broad categories.

Dog General Anesthesia

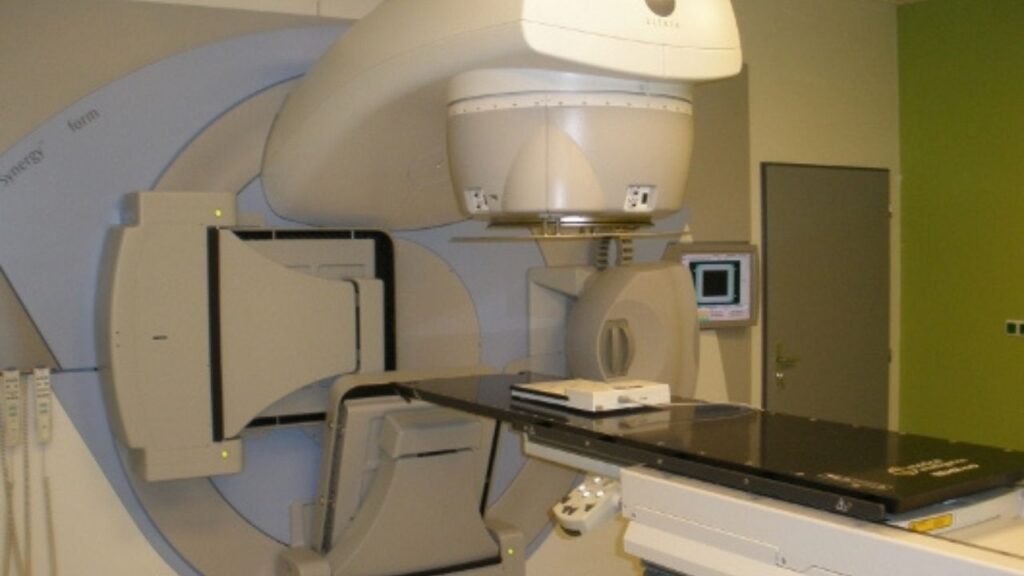

General anesthesia is used to place a dog into an unconscious state so they cannot move and do not feel pain during certain procedures. This is required for major procedures such as surgery and is also used for diagnostic tests when the dog needs to be still, such as during a CT scan or when receiving radiation treatments.1

While the procedure for general anesthesia will vary slightly depending on the individual dog’s needs and the doctor’s experience and preferences, the basic protocol is as follows:

- Premedication is given, usually by an injection into the muscle (IM), to relax the dog and allow for intravenous (IV) catheter placement. For dogs who get really stressed at the vet’s office, your vet may send home an oral sedative for you to give before you come in for the appointment.

- The dog’s leg is shaved and cleaned, and an IV catheter is placed into a vein. This allows medications to be delivered quickly and directly into the bloodstream. There may be more than one IV catheter in place.

- One or more medications are given through the IV catheter to induce anesthesia (make the dog fall asleep) and allow a breathing tube to be placed in the trachea (windpipe).

- Once the breathing tube is placed, the dog is kept unconscious with medications that are inhaled, along with oxygen, through the breathing tube.

- Vital signs are monitored continuously throughout the procedure, including breathing, heart rate, temperature, and blood pressure.

- IV antibiotics, pain medications, and any other necessary medications are given as appropriate for the specific procedure being performed.

- Once the procedure is complete, the inhaled anesthesia medication is turned off to allow the dog to wake up.

- Once the dog is awake enough to swallow and start to move, the breathing tube is removed, and the dog is moved to the recovery area. Veterinary staff will continue to monitor vital signs until the dog is fully awake and showing no signs of complications.

Many different drugs can be used during the various stages of anesthesia. Your veterinary team will select a drug protocol based on your dog’s specific needs, as well as their preferences.

If your dog has had an issue with a particular drug before, mention it! Your vet can change to a different protocol that your dog will hopefully tolerate better.

Some common drugs used for anesthesia in dogs include:

- Butorphanol (sedation, premedication)

- Dexmedetomidine (sedation, premedication)

- Isoflurane (gas anesthesia)

- Ketamine (sedation, premedication, inducing anesthesia)

- Lidocaine (local anesthetic)

- Midazolam (sedation, premedication, inducing anesthesia)

- Propofol (inducing and maintaining anesthesia)

- Sevoflurane (gas anesthesia)

Anesthesia for dogs doesn’t have to be scary. One weird nap for your dog, one amazing opportunity for vets to provide lifesaving medical care. Technician anesthesia specialist Tasha McNerney answers all of your questions in this episode of Dog Cancer Answers.

Sedation

Sometimes general anesthesia is more than is needed for a certain procedure or test and sedation can be used instead. Sedation protocols vary widely depending on the procedure being performed and the needs of the individual dog.

When a dog is sedated, she is given medications either IM (into a muscle) or IV (into a vein) to decrease awareness and pain sensation and minimize movement, but she is not fully asleep. This does not require a breathing tube, but vital signs are still monitored.

Once the procedure is complete, some of these medications can be reversed so the dog can wake up faster.

Sedation is commonly used to help a dog relax and be still for diagnostic tests that may be stressful or uncomfortable, like x-rays or ultrasound.

Local Anesthesia

Local anesthesia is another type of anesthesia used to numb a small area of the body. This is usually done with an injection of a local anesthetic (such as lidocaine) near the nerves to block pain sensation in that area.

Local anesthesia is sometimes used for small, minimally painful procedures such as a punch biopsy of a tumor on the skin. It can also be used during general anesthesia or sedation as additional pain control to the area being worked on. For example, to remove a tumor in the mouth, local anesthesia may be used to block the nerves supplying the teeth and jaw near the tumor to make it less painful after the dog wakes up.

Sedation is commonly used to help a dog relax and be still for diagnostic tests that may be stressful or uncomfortable

When Dog Anesthesia Is Recommended

Some level of anesthesia will be recommended for any procedure that is painful or that requires the dog to stay still.

If your dog needs surgery to remove a tumor, general anesthesia will be required. General anesthesia will also be required for any procedure that requires your dog to be absolutely still, like radiation treatments and advanced diagnostics like a CT scan or MRI.

If your dog is nervous or in pain, sedation will be recommended for some diagnostic tests like x-rays or ultrasound. Sedation may also be recommended for a variety of other procedures like small biopsies of skin tumors.

Local anesthesia is likely to be performed in combination with general anesthesia when performing a major surgery, but may also be used for smaller, minimally invasive procedures like biopsies of skin masses.

How Dog Anesthesia Works to Put Your Dog Under

Anesthesia allows your dog to have life-saving procedures and diagnostics that are painless and stress-free. Many of these procedures would be impossible without anesthesia.

Anesthesia drugs cause temporary unconsciousness by interrupting nerve signals throughout the body, keeping your dog in a “coma-like” 2 state. During this, they are relaxed and cannot feel pain.

This anesthetized state also reduces breathing, heart rate, and blood pressure, and interferes with the body’s ability to regulate normal functions like fluid levels and temperature.

There are different depths (or “planes”) of anesthesia:

- Plane 1 – superficial anesthesia in which the blink reflex is still present, and muscles retain tone.3

- Plane 2 – surgical anesthesia in which the blink reflex is absent, muscle tone is relaxed, and eyes remain rotated downward toward the nose.3

- Plane 3 – deep anesthesia in which there is complete muscle relaxation, breathing is shallow, and may require assistance.3

A surgical plane of anesthesia is required for most invasive procedures. Your dog will be continually monitored, and medications adjusted as needed to keep her at an appropriate anesthetic depth.

There’s a bunch of things you should do to get your dog ready for surgery and help the day go smoothly. Veterinary technician Kate Basedow has tons of tips in this episode of Dog Cancer Answers.

Using Anesthesia During Cancer Treatments

Anesthesia is used for:

- any cancer requiring surgery

- any cancer requiring advanced diagnostic procedures

- any cancer for which radiation is part of the treatment plan

How to Get the Best Results from Anesthesia

If your dog is having anesthesia, your veterinarian will give you instructions on how to prepare her for it. This will typically include an exam before the procedure is scheduled and another exam the day of the procedure to ensure your dog has not had any major changes with her heart and lungs or her overall health status.

Your vet will also recommend preanesthetic bloodwork to make sure there are no major changes with blood counts or internal organs that would increase the risk of anesthesia.

One of the most important things will be to withhold food before the procedure. This will help prevent vomiting and possible aspiration (inhaling stomach contents into the lungs) which can cause pneumonia. Traditionally many vets instructed owners to fast their dogs for 12 hours or more, but newer recommendations from the American Animal Hospital Association recommend shorter fasting times of 6-8 hours for most patients, and even shorter times for really young patients and diabetics.4

If your dog is having surgery, it is recommended to stop any anti-coagulant medication for at least one week before surgery to prevent excessive bleeding.

Some other supplements and medications that are recommended to discontinue before surgery include:

- Some NSAIDs (meloxicam, previcox, carprofen (Rimadyl), etogesic, deracoxib (Deramaxx)) and Adequan

- Omega-3 fatty acids/fish oil/krill oil

- Curcumin or turmeric

- Garlic supplements

- Maritime pine bark

- Apocaps

- Bromelain

- Wobenzyme-M

- Skullcap

These have a lower risk of causing additional bleeding but are usually recommended to stop before surgery just to be safe. Talk to your veterinarian before any surgery to determine which medications and supplements should be paused and which ones you should continue to give.

If your dog has had an issue with a particular drug before, mention it! Your vet can change to a different protocol that your dog will hopefully tolerate better.

Home Care After Dog Anesthesia

Home care after anesthesia will vary widely depending on what procedure(s) your dog had. For example, recovery from anesthesia for a CT scan will be much less involved than recovery from abdominal surgery for most dogs.

In general, you should be prepared for GI issues such as:

Most veterinarians will send you home with anti-nausea medications to have on hand in case it is needed.

Having a bland diet at the ready, either a commercially prepared prescription diet or low-fat human foods like chicken and rice, will be helpful if your dog has nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea. Canned pumpkin or another fiber source may be helpful for constipation.

If your dog needs medications after the procedure, some special foods (pill pockets, cheese, deli meat, etc.) may be helpful for getting your dog to take her medications.

If your dog is having surgery, they will usually need to have their movement restricted until the incision heals – at least 10-14 days. A quiet place to put a crate or pen will help your dog rest during the recovery period. Some dogs will also be incontinent for a period of time after a procedure and will need frequent cleaning.

Some dogs will be wobbly after anesthesia and mobility aids such as a sling, harness, or ramp will be necessary to help them get up and move around. This is especially true for dogs that already have mobility issues, neurologic disease, and often for amputees while they adjust to having three legs.

Any grogginess from anesthesia typically resolves within 24 hours, but ill or elderly pets may take longer to fully recover.

Waking up from the anesthesia isn’t the end of surgery recovery. Learn how to care for your dog as she heals over the next two weeks in this episode of Dog Cancer Answers.

Follow Up Appointments

There is usually no need for follow-up appointments due to anesthetic use. Other follow-up appointments will vary depending on the procedure, type of cancer, and treatment plan.

If your dog had surgery, the sutures or staples will need to be removed in 10-14 days.

If your dog had a tumor removed, it will be sent to the lab for analysis and follow up will depend on the lab results and the recommended next steps.

When to Not Use Anesthesia in Dogs

If your dog is very sick, she may not be well enough to undergo anesthesia.

For example, dogs with a ruptured abdominal mass such as hemangiosarcoma may be compromised from severe blood loss and must be stabilized before going under anesthesia. Stabilization may include fluids to improve blood pressure, oxygen therapy, and pain or sedative medications as needed.

Dogs with concurrent illnesses such as certain heart diseases, liver, or kidney disease may not be able to withstand anesthesia or will need an anesthesia protocol designed for their specific needs.

While age is not a disease, many older dogs are slower to recover from anesthesia or have concurrent issues that make anesthesia riskier. Your veterinarian will take all of these factors into consideration when discussing the pros and cons of anesthesia with you.

Where to Get Good Anesthesia for Your Dog

Anesthesia at some level is available through almost all veterinary practices. Advanced diagnostics and complicated surgical procedures for which anesthesia is required are usually performed by veterinary specialists at a specialty hospital or teaching hospital (veterinary school).

Dog Anesthesia Side Effects

Anesthesia is never without risk, but in the hands of an experienced practitioner the risk can be minimized.1

Minor risks of anesthesia include:

- Stiffness from being in one position for a prolonged time during the procedure

- Coughing or throat irritation from the breathing tube

- Razor burn at the catheter site or surgery site

- Soiled fur from urine or fecal matter leakage during surgery

Major risks of anesthesia may include:

- Kidney damage

- Brain damage

- Stroke

- Severe hypotension (low blood pressure)

- Allergic reactions to medications

- Problems with heart rate and rhythm

Anesthesia interferes with normal body functions, so vital signs must be monitored during anesthesia and abnormalities corrected as needed. Monitoring may include:

- Heart rate and rhythm (ECG)

- Breathing rate and oxygen levels

- Body temperature

It is common for dogs to feel nauseous and vomit when premedications are first administered. It is very important to withhold food as directed by your vet before anesthesia to prevent vomiting and possible aspiration once your dog is under anesthesia.

After waking up from anesthesia it is common for dogs to seem disoriented and wobbly. Some may even vocalize. Nausea after anesthesia is also common. Your veterinarian may give medications to help keep them calm or to treat nausea while they are waking up.

A full team helps to make sure your dog is safe during anesthesia.

Cost of Anesthesia for Dogs

Costs of anesthesia will vary widely and depend on many factors including the procedure for which anesthesia is being performed, the length of time the dog is under anesthesia, and how long they will be hospitalized.

For example, sedation for x-rays will cost much less than a complicated mass removal that takes several hours under general anesthesia.

Some options to help dog guardians pay for these necessary procedures include:

- Many veterinary hospitals accept CareCredit, a credit card designed specifically for healthcare expenses, including veterinary bills. It is a high-interest credit card, but for expenditures over a certain amount, there are usually special financing options with 0% interest for a period of time – usually 6, 9, or 12 months. If you make payments on time each month and pay off the total before the end of the special financing period, you will pay no interest.

- Pet insurance is another option for offsetting the costs of pet care and there are many companies and types of plans to choose from. It is important to note, however, that few plans cover pre-existing conditions, so your dog must already be enrolled before getting sick for the plan to cover expenses associated with her illness.

- Assistance funds. The Humane Society of the United States has a comprehensive list of assistance funds available to pet owners who are struggling to afford medical care for their pets.

- Some veterinary hospitals have payment plans available, especially if you are a long-term client with a proven payment history. Ask your vet if this is an option for you.

- Dressler D, Ettinger S. In: The Dog Cancer Survival Guide: Full Spectrum Treatments to Optimize Your Dog’s Life Quality and Longevity. Maui, HI: Maui Media, LLC; 2011.

- Carpenter R. How Does Anesthesia Work? VIN. https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/. Published May 19, 2020. Accessed January 7, 2023.

- Ubiali MLC, Meirelles GP, Vilani JM, et al. Evaluation of the anesthetic depth and bispectral index during propofol sequential target-controlled infusion in dogs. Vet World. 2022;15(3):537-542. doi:10.14202/vetworld.2022.537-542

- Grubb T, Sager J, Gaynor JS, et al. 2020 AAHA anesthesia and monitoring guidelines for dogs and cats*. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association. 2020;56(2):59-82. doi:10.5326/jaaha-ms-7055

Topics

Did You Find This Helpful? Share It with Your Pack!

Use the buttons to share what you learned on social media, download a PDF, print this out, or email it to your veterinarian.