Osteosarcoma in dogs is an aggressive bone cancer. It is a scary and devastating diagnosis, but there are treatment options available that can extend and improve the quality of your dog’s life. Osteosarcoma in dogs is used as a model for the same cancer that affects children, so there may be more innovative treatment options on the horizon.

Key Takeaways

- Though it varies based on many factors, most dogs who have osteosarcoma and are treated with amputation and chemotherapy live about a year.

- The first sign of osteosarcoma in dogs is usually pain and limping that gets worse despite pain control. X-rays will usually show a mass growing in the painful bone.

- Osteosarcoma is very aggressive and will attack the bone and quickly spread to other parts of the body, especially the lungs. By the time most dogs are diagnosed with osteosarcoma, and a bone tumor is found, it has already spread to the lungs.

- Nothing is impossible, but most dogs with osteosarcoma have a bad prognosis. If caught early, and treated aggressively, some dogs can live for a few months to years.

- Osteosarcoma in dogs is very, very painful. No dog should experience this disease without pain control throughout all stages of treatment.

- Osteosarcoma is a painful, aggressive cancer that often spreads to the lungs. Most dogs with osteosarcoma will die either from euthanasia — because the pain is too much to bear — or from cancer in the lungs interfering with the ability to breathe.

- Most dogs who are diagnosed with osteosarcoma are 6 to 10 years old, though dogs at any age can get it and giant breed dogs tend to get it younger.

- Dogs with osteosarcoma need adequate pain control, a healthy diet, and lots of love, no matter what treatment option you choose.

An Overview of Canine Osteosarcoma and Its Many Locations

Osteosarcoma (OSA) is the most common type of bone cancer in dogs. In the veterinary field, it is often just called “osteo” for short. Other cancers can affect the bones, but the likelihood that a cancerous bone mass is osteosarcoma is around 80%.

Osteosarcoma starts when osteoblasts, the cells that make bone, undergo an error in replication and become cancerous. Since the onset is at the cellular level and bones are deep in the body, you will not see a tumor until there has been significant growth. This, and the natural stoicism of dogs, makes early detection of osteosarcoma in dogs difficult.

Where Osteosarcoma Occurs in the Body

Osteosarcoma can affect any bone. However, 75% of cases are found in the limbs, which is called appendicular osteosarcoma.

- Common locations are the proximal humerus (the part closest to the shoulder) and the distal femur (the part closest to the knee).

- Appendicular osteosarcoma is also commonly found in the distal radius (the part closest to the “wrist) and the proximal and distal tibia (both ends of the “shin bone”).

Other common areas for canine osteosarcoma are flat bones like ribs or skull bones. Tumors in these locations are called axial osteosarcoma. Oral or maxilla facial osteosarcoma tends to be less likely to metastasize than appendicular osteosarcoma, but it is still locally aggressive.6

First Signs of Osteosarcoma in Dogs

The first sign of appendicular osteosarcoma may simply be limping, which gets increasingly worse with time. Eventually, a firm boney mass can be felt.

What If You Don’t Treat Osteosarcoma?

Since cancerous bone is not healthy it is more likely to fracture, so if left untreated your pet may develop what we call a pathologic fracture – meaning the bone broke due to the underlying disease, not trauma. In axial osteosarcoma, you will feel a firm mass develop on the bone affected.

The typical age of diagnosis of appendicular osteosarcoma is around 6-10 years old but there is also a peak in dogs around 1-2 years of age. Large and giant breed dogs are at higher risk and tend to develop osteosarcoma at younger ages. There are certain predisposed breeds which are discussed below.

Canine Osteosarcoma Progression

Osteosarcoma in dogs is very painful. As the bone tumor grows, your dog will become unable to use the affected leg. As the bone weakens, it may fracture.

Osteosarcoma is an aggressive cancer that will metastasize — or spread to other parts of the body. Unfortunately, 80% of untreated dogs with osteosarcoma will die from lung metastasis.14

Stats and Facts

- 10,000 dogs a year are diagnosed with osteosarcoma.16

- 80% of malignant bone masses in dogs are osteosarcoma.14

- 64% of osteosarcomas affect front or rear limbs (radius or femur), while 28.5% affect the ribs or skull and 7.5% affect internal organs.14

- 90% of dogs with limb osteosarcoma develop lung metastasis12 and 80% of dogs die from lung metastasis.14

- Dogs neutered or spayed before 1 year of age had a 1 in 4 lifetime risk for osteosarcoma and were more likely to develop osteosarcoma than intact dogs.4,12

- 90% of dogs with osteosarcoma already had micro-metastasis at the time of diagnosis.14

- Median survival time with amputation and chemotherapy is 10-12 months.12

- Median survival time in dogs with pulmonary (lung) metastasis is 59 days.12

- ALP (liver enzyme) elevation at time of diagnosis is a negative prognostic indicator — meaning that these dogs tend to do more poorly.2

- Monocytosis (a high level of the immune cells called monocytes) found on blood work at time of diagnosis is a negative prognostic factor — meaning that these dogs tend to do more poorly.17

- Palliative radiation leads to pain relief in 74% of dogs and may last about 73 days.8

Causes

Like most cancers, the exact cause of osteosarcoma in dogs is unknown. There are likely several factors including genetics, environment, and bad luck. Recently there are some studies suggesting early castration may increase the risk of OSA in dogs.

Risk Factors

- Dogs greater than 40 kg (88 pounds) have increased risk.10,1

- Early spay/neuter may increase risk in certain breeds, more commonly in males.4

- Small breed dogs are less likely to develop osteosarcoma, but if they do, they tend to survive longer. 1

- The Rottweiler and Great Dane are ten times more likely to develop osteosarcoma compared to mixed breeds.5

- There is possibly an increased risk of osteosarcoma occurrence at previous fracture sites where an older generation of hardware was used to repair.13

Dog breeds less likely to get osteosarcoma include:5

- Bichon Frise

- French Bulldog

- Cavalier King Charles

Dog breeds that have an increased risk for osteosarcoma include:14,5

- Irish wolfhound

- Leonberger

- German Shepherd

- Boxer

- Doberman

- Irish setter

- Rottweiler

- Great Dane

Symptoms of Osteosarcoma in Dogs

The first sign of appendicular canine osteosarcoma (bone cancer in a leg) will be lameness. That gets worse despite treatment with pain medications and rest. You may notice your dog occasionally limping at first, which will then get worse over time.

You may feel a thickened or lumpy area of bone.

Dogs with very aggressive osteosarcoma may start coughing or have exercise intolerance once cancer has spread from the bone to the lungs.

Diagnosis of Osteosarcoma in Dogs

The first step toward diagnosis of canine osteosarcoma is radiographs. Your veterinarian will often notice a typical pattern often seen on x-rays. The bone will appear lytic (eaten away) and there will be a reactive sunburst pattern where the tumor cells have taken over normal bone. There may also be a pathologic fracture of the bone noted.

The changes from osteosarcoma do not cross a joint space. This means if your veterinarian sees abnormalities on both sides of a joint on x-rays, it is less likely to be osteosarcoma.

Sometimes in the early stages of osteosarcoma, the abnormalities can be subtle or very hard to see on x-rays, even if your dog is limping. In these cases, it is normal to treat with pain meds and rest, then retake radiographs a few weeks later to look for any changes.

A bone biopsy is the only way to definitively diagnose osteosarcoma in dogs. This can be done with a large bore needle to take cells directly from the bone tumor. It is a very painful procedure and anesthesia is needed. For these reasons — and because the appearance of osteosarcoma on x-rays is so distinctive — many veterinarians will not recommend a bone biopsy.

Another option for confirming a diagnosis of osteosarcoma in dogs is to send out a cytology (obtained by FNA) for ALP staining. This method is less invasive than a full bone biopsy. It is less risky for the dog and is very accurate.18

Diseases that can resemble canine osteosarcoma based on symptoms and x-rays include synovial cell carcinoma (which occurs on both sides of joint), chondrosarcoma (cancer of the cartilage in bones), or fungal infections. Squamous cell carcinoma is also possible but that tends to be in the facial bones or toes.

All of these diseases have similar treatment recommendations, which is to surgically remove the diseased bone (this often requires amputation). This is another reason many veterinarians do not recommend a bone biopsy, but prefer to move directly to surgery, then send the tumor to the lab for more analysis. The histopathology of the mass will confirm diagnosis and help guide treatment options.

Prognosis and Staging

The prognosis for a dog with osteosarcoma varies depending on the severity of the cancer at the time of diagnosis and what treatment options are pursued.

Here are the median survival times (MST) for several different scenarios:

- No treatment: 60 days in one study13 and 138 days in another study.14

- With metastasis to the lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis: 48 days.14

- Amputation alone: 3-5 months.8

- Amputation and chemotherapy: 8-10 months.8,12

- With evidence of metastasis to the lungs: 59 days.12

Staging is the process of determining the extent and severity of your dog’s cancer. This information may impact which treatments your veterinarian recommends and which ones you decide to pursue with your dog. Tests commonly used for staging osteosarcoma include:

- Chest radiographs (x-rays) to look for metastatic disease. This part of staging is definitely worthwhile as it does not cost much more, it helps predict potential outcomes, and may reveal an increased risk for anesthesia.

- Bloodwork (full chemistry, complete blood count, and clotting times) to evaluate any other diseases or health problems your dog may have. This will also show the ALP (a type of liver enzyme) value which helps predict outcomes. These blood tests are also required before anesthesia and surgery.

- Some veterinarians will recommend a biopsy of the local lymph nodes. It may not be useful in appendicular osteosarcoma (when osteosarcoma is in a limb), since amputation is the next step, and the lymph node will be removed anyway. Lymph node biopsy may be more useful in axial osteosarcoma (bones of the head, spine, and chest).

- Some veterinarians will recommend an abdominal ultrasound to look for metastasis in internal organs. It may not be very useful since osteosarcoma in dogs most often spreads to the lungs and is found on x-rays.

- Advanced imaging (nuclear scintigraphy, CT) can be used to stage but is not often recommended. These tests can be expensive and often will not change the treatment plan.

Treatment

Cancer treatment in dogs is not usually about getting a “cure.” Instead, the focus is on improving and maintaining quality of life while also hopefully extending the dog’s life beyond what would happen if the cancer wasn’t treated.

Surgery

Amputation (surgically removing the limb) is the gold-standard surgical treatment for osteosarcoma in dogs. There are several reasons for this:

- There is no way to remove the tumor without removing the whole bone.

- It allows for large margins around the tumor.

- It removes the source of pain.

- It is quicker, with fewer complications, less expensive, and an easier recovery than limb- sparing procedures.12-14,2

Limb sparing is an alternative surgery to surgically removing the entire limb. This surgery involves removing the tumor and surrounding bone, then implanting hardware or grafting from another healthy bone into the space.

Limb sparing surgery is complicated and often not very successful. Up to half of limb spare surgeries will have complications and even more will fail14. The affected joint will often fuse, meaning there will be permanent loss of mobility around the joint after the surgery. Because of this, limb sparing surgery is usually only done in distal radial masses (the long bone near the wrist).

There was a recent study using 3D printing to make personalized implants for limb spare surgeries. This new technology shows promise, but there were still complications, and it was a pilot study of only 5 dogs.11 More studies need to be done before the public can benefit from it.

Chemotherapy

By the time an osteosarcoma tumor has been found in your dog’s bone, cancer has likely already spread to the rest of the body (usually the lungs), even if it is not seen on x-rays. For this reason, chemotherapy is often recommended after surgery.

A variety of chemotherapy drugs have been used and studied in dogs:

Carboplatin (with amputation)

- Median survival time (MST) is 307-365 days2,14 versus 138 days with surgery alone.14

- Given intravenously every 3-4 weeks for four to six treatments.

- Median survival time (MST) is 322-400 days.2,14

- Given intravenously every 3 weeks and does have a risk of causing kidney damage.

- Median survival time (MST) is 303-365 days.2,14

- Given intravenously every 2 to 3 weeks for four to six treatments.

- Heart issues can develop, so it is best to have an echocardiogram prior to treatment.

Doxorubicin and Carboplatin or Cisplatin together 14

- Similar median survival time (MST) when used together as when used alone.

- Increased risk of side effects when used together.

- A recent study in 2017 did not show an increase in median survival time (MST) in cases of osteosarcoma that has already spread to the lungs.9

- There is another clinical trial currently underway.

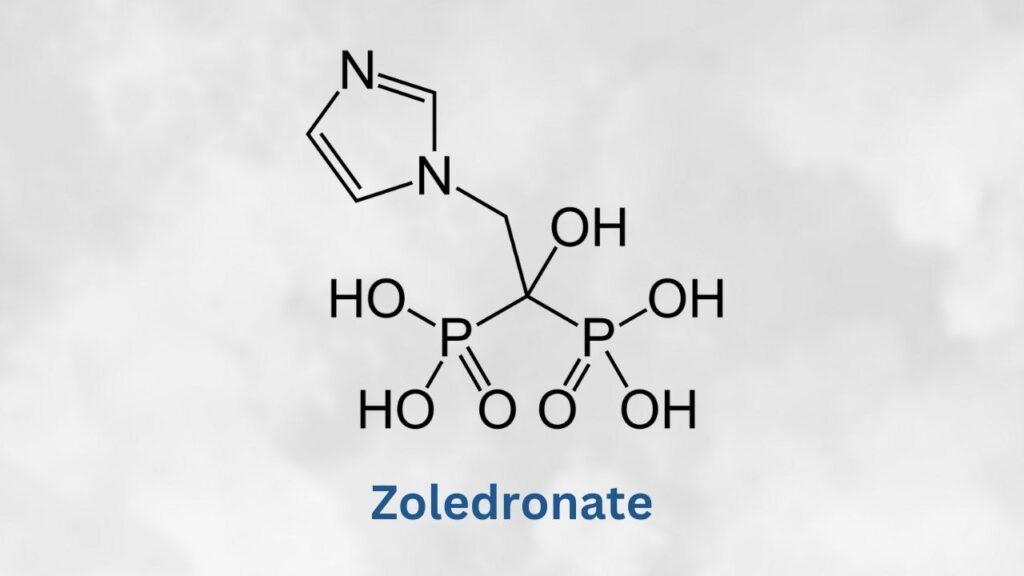

Bisphosphonates

- These drugs can decrease pain and hypercalcemia and may be toxic to cancer cells.12

- Pamidronate (a drug used to treat osteoporosis) can kill osteosarcoma cell lines in vitro (lab tests, not in a live body) but when used with chemotherapy there was no change in outcome.14

- Case studies looking at zoledronate (another bisphosphonate) were promising but a follow-up study looking at dogs with metastatic osteosarcoma had variable results. These studies were difficult to interpret, as they had few dogs participating, with variable treatment histories. More studies are needed.12

Radiation

Radiation can be used to kill lingering cancer cells after surgery and can also be used for palliation (reduce symptoms and maintain quality of life).

Radiation combined with chemotherapy is more effective than radiation on its own8. Radiation combined with bisphosphonates can provide pain relief as well.

Radiation may best be used in dogs with osteosarcoma for palliation – to decrease pain and the soft tissue component of tumor size. A recent study found that palliative radiation can lead to a reduction of pain with a median response time of 73 days.8 Treatment typically involves 2-4 doses once per week.8

Immunotherapy

Natural Killer Cell Immunotherapy is currently still in the clinical trial and research stage but may be more widely available soon. Various other immunotherapy approaches are being researched but nothing clinically useful yet.8

Vaccine

There is currently no commercially available vaccine to prevent osteosarcoma. All vaccines used to treat osteosarcoma are currently in the study phase.

ELIAS Animal Health has an autologous vaccine for osteosarcoma in dogs that has just completed clinical trials. T-cells — which are important immune cells — are collected from the dog’s tumor, engineered in the laboratory for anti-tumor activity, then given back to the dog in the form of a vaccine. Watch for results of the trial at https://eliasanimalhealth.com/clinical-trials/canine-osteosarcoma/.

Elanco has also developed a vaccine for osteosarcoma that uses listeria bacteria to stimulate the immune system to attack osteosarcoma cancer cells. This is a live vaccine and there may be a small risk of listeria infection in humans. In a recent study, 8% of dogs became positive for listeria but overall, the vaccine had minimal adverse effects.19 This vaccine is available at some veterinary universities, so if you are interested, contact the one nearest you for more information.

Diet

There are no specific dietary recommendations for dogs with osteosarcoma. Like all dogs with cancer, feeding a complete and balanced diet is the best way to support your dog’s health.

Supplements

There are a few supplements that may be beneficial for dogs with osteosarcoma. General pain management and anti-inflammatory supplements can be used such as curcumin, fish oil, and hemp/CBD.

If your dog is receiving chemotherapy, other supplements may be helpful to address side effects.

Alternative Therapies

Acupuncture may be beneficial for pain management.

There are several herbal therapies available online. Most had positive anecdotal evidence, but minimal research or studies to determine effectiveness. In a case of aggressive cancer like osteosarcoma in dogs, if you want to try herbal therapy or other supplements, please consult your veterinarian first.

Final Stages of Osteosarcoma in Dogs

Bone cancer is aggressive and extremely painful. If no treatment is elected, then most dogs are euthanized due to pain related to the tumor itself or fracture related to the tumor. Other dogs may die from the spread of cancer to the lungs.

If treatment is elected, most dogs have a longer survival time, although how much varies greatly. Most dogs will eventually die from complications of osteosarcoma spreading to the lungs or other parts of the body.

Osteosarcoma is one cancer where euthanasia is almost always far kinder than a natural death. Discuss with your veterinarian how to evaluate your dog’s pain levels, and frequently assess his quality of life during the treatment process. It may be a good idea to “adopt a hospice mindset” right from the beginning with this cancer type, as that will help you manage your expectations and your treatment choices.

Prevention Strategies

There is no absolute way to prevent osteosarcoma, although there may be ways to lower the risk. In high-risk breeds, consider delaying spay or neuter surgery until at least one year of age and allow females to go through at least one heat cycle. Early evidence suggests this may reduce risk, although it is not a guaranteed prevention strategy.

- Amsellem PM, Selmic LE, Wypij JM, et al. Appendicular osteosarcoma in small-breed dogs: 51 cases (1986-2011). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2014;245(2):203-210. doi:10.2460/javma.245.2.203https://bonecancerdogs.org/

- Boerman I, Selvarajah GT, Nielen M, Kirpensteijn J. Prognostic factors in canine appendicular osteosarcoma – a meta-analysis. BMC Vet Res. 2012;8:56. Published 2012 May 15. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-8-56

- Brooks W. Osteosarcoma in dogs. VIN. https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4951687. Accessed December 5, 2022.

- Cooley DM, Beranek BC, Schlittler DL, Glickman NW, Glickman LT, Waters DJ. Endogenous gonadal hormone exposure and bone sarcoma risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11(11):1434-1440.

- Edmunds GL, Smalley MJ, Beck S, et al. Dog breeds and body conformations with predisposition to osteosarcoma in the UK: a case-control study. Canine Med Genet. 2021;8(1):2. Published 2021 Mar 10. doi:10.1186/s40575-021-00100-7

- Farcas N, Arzi B, Verstraete FJ. Oral and maxillofacial osteosarcoma in dogs: a review. Vet Comp Oncol. 2014;12(3):169-180. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5829.2012.00352.x

- Kisseberth WC, Lee DA. Adoptive Natural Killer Cell Immunotherapy for Canine Osteosarcoma. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:672361. Published 2021 Jun 7. doi:10.3389/fvets.2021.672361

- Poon AC, Matsuyama A, Mutsaers AJ. Recent and current clinical trials in canine appendicular osteosarcoma. Can Vet J. 2020;61(3):301-308.

- Regan DP, Chow L, Das S, et al. Losartan Blocks Osteosarcoma-Elicited Monocyte Recruitment, and Combined With the Kinase Inhibitor Toceranib, Exerts Significant Clinical Benefit in Canine Metastatic Osteosarcoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28(4):662-676. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-2105

- Schmidt AF, Nielen M, Klungel OH, et al. Prognostic factors of early metastasis and mortality in dogs with appendicular osteosarcoma after receiving surgery: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Prev Vet Med. 2013;112(3-4):414-422. doi:10.1016/j.prevetmed.2013.08.011

- Séguin B, Pinard C, Lussier B, et al. Limb-sparing in dogs using patient-specific, three-dimensional-printed endoprosthesis for distal radial osteosarcoma: A pilot study. Vet Comp Oncol. 2020;18(1):92-104. doi:10.1111/vco.12515

- Smith AA, Lindley SES, Almond GT, Bergman NS, Matz BM, Smith AN. Evaluation of zoledronate for the treatment of canine stage III osteosarcoma: A phase II study [published online ahead of print, 2022 Nov 18]. Vet Med Sci. 2022;10.1002/vms3.1000. doi:10.1002/vms3.1000

- Stilwell, Natalie DVM. Out on a limb: Osteosarcoma in dogs and cats. DVM 360. https://www.dvm360.com/view/out-limb-osteosarcoma-dogs-and-cats. Published April 28, 2020. Accessed December 6, 2022.

- Szewczyk M, Lechowski R, Zabielska K. What do we know about canine osteosarcoma treatment? Review. Vet Res Commun. 2015;39(1):61-67. doi:10.1007/s11259-014-9623-0

- Westermarck E, Wiberg M. Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in the dog: Historical background, diagnosis, and treatment. Topics in Companion Animal Medicine. 2012;27(3):96-103. doi:10.1053/j.tcam.2012.05.002

- Wycislo KL, Fan TM. The immunotherapy of canine osteosarcoma: a historical and systematic review. J Vet Intern Med. 2015;29(3):759-769. doi:10.1111/jvim.12603

- Tuohy JL, Lascelles BDX, Griffith EH, Fogle JE. Association of canine osteosarcoma and monocyte phenotype and chemotactic function. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2016;30(4):1167-1178. doi:10.1111/jvim.13983

- Barger A, Graca R, Bailey K, et al. Use of alkaline phosphatase staining to differentiate canine osteosarcoma from other vimentin-positive tumors. Veterinary Pathology. 2005;42(2):161-165. doi:10.1354/vp.42-2-161

- Musser, ML, Berger, EP, Tripp, CD, Clifford, CA, Bergman, PJ, Johannes, CM. Safety evaluation of the canine osteosarcoma vaccine, live Listeria vector. Vet Comp Oncol. 2021; 19: 92– 98.

Topics

Did You Find This Helpful? Share It with Your Pack!

Use the buttons to share what you learned on social media, download a PDF, print this out, or email it to your veterinarian.