Leukemia is an aggressive blood cancer, but thankfully it is uncommon in dogs. The treatment options and likely outcomes vary widely based on the type of leukemia your dog has.

Key Takeaways

- Leukemia is a cancer of the white blood cells (immune cells) of dogs. We do not know what causes it, but we suspect it is a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

- The expected life span for dogs with leukemia varies widely based on what kind of leukemia they have. In general, dogs with acute (sudden onset) leukemia are very sick and die quickly, but dogs with chronic (slow onset) leukemia can live for months – or even years – with the disease.

- How treatable leukemia is in dogs depends on what kind of leukemia they have and how sick they were when the leukemia was diagnosed. Dogs with acute (sudden onset) leukemia who feel very sick do not do very well with treatment, but dogs with chronic (slow onset) leukemia who do not feel very sick, often do not need treatment at all.

- Dogs with leukemia are not likely to be in extreme pain, but depending on the type of leukemia, some of these dogs can feel quite miserable. The most common symptoms seen with acute (sudden onset) leukemia include vomiting, diarrhea, lethargy, and loss of appetite. Many dogs with chronic (slow onset) leukemia have milder symptoms or no symptoms at all.

- The cost to treat leukemia varies widely based on the type of leukemia, how healthy your dog is at the time of diagnosis and what treatment options you choose. Some dogs are either so sick that they are euthanized, or are not feeling sick at all, and don’t need treatment. Other dogs require a lot of testing, follow-up, and treatments (usually chemotherapy). Ask your veterinarian which scenario applies to your dog.

- Leukemia is very uncommon in dogs. Dogs of any breed and age can get leukemia, but certain breeds may have a slightly increased risk: Golden Retrievers, German Shepherds, Pit Bulls, English Bulldogs, Boxers, Shih Tzus, Jack Russell Terriers, Dachshunds, and Cocker Spaniels.

The Many Types of Leukemia in Dogs

Leukemia is a type of cancer affecting humans and animals in which white blood cells essentially go into overdrive. “Leuk” means white, and “emia” means blood. Leukemia in dogs is rare, thankfully.

In a healthy body, white blood cells act as part of our immune defense system, fighting infection and injury and supporting the body in times of stress. In leukemia, the bloodstream is flooded with so many cancerous white blood cells that the body stops producing enough of the other important cells needed to function properly.1

Dogs can have many types of leukemia, and the terms can be confusing, so we’ll break it down for you.

Chronic or Acute? Lymphoid or Myeloid?

Leukemia is categorized as either chronic or acute:

- Acute means “quick onset of symptoms.” Acute leukemia typically involves immature cells in the bone marrow.

- Chronic means “slow onset of symptoms.” Chronic leukemia typically involves mature lymphocytes in the bone marrow or circulating throughout the body.

It’s also categorized as either lymphoid or myeloid:

- Lymphoid means the cancerous cells were supposed to become lymphocytes, a specific type of white blood cell.

- Myeloid means the cancerous cells were supposed to become red blood cells and non-lymphocyte white blood cells.6

Combining these terms, there are five main leukemias described in dogs:4

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL)

- Chronic myeloid leukemia (CML)

- Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)

- Acute myeloid leukemia (AML)

- Acute undifferentiated leukemia (AUL), meaning it is uncertain where it started

In general, dogs with chronic leukemia progress gradually and can have a longer survival time, while those with acute leukemia become sick quickly with a rapid progression and poor prognosis.2

Type of Lymphocyte

To make it even more complicated, Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) and Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL) can be further classified by what type of lymphocyte the original cell was: B-cell, T-cell, or natural killer (NK) cell.6

Dr. Demian Dressler takes a call about Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia on Dog Cancer Answers.

Studying Dogs and Humans with Leukemia

Since leukemia affects humans and dogs, studies involving one species can benefit the other. Comparative oncology is a field where researchers use studies from one species and apply them to develop studies in another.

The National Cancer Institute has used comparative oncology to examine the most common blood cancers (leukemia and lymphoma) and other cancer types. The more research and studies performed on both species, the more likely new, successful treatment strategies will be developed.3

Stats and Facts

- In dogs, chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) and Acute Undifferentiated Leukemia (AUL) are both rare leukemias.4

- Leukemia is relatively uncommon in dogs.

- Acute leukemias are more common than chronic.7

- In acute leukemia, the cancerous white blood cells are immature and proliferate more rapidly. In chronic leukemia, the white blood cells are more mature, and progression typically occurs more slowly.5

- Lymphoid leukemias are believed to be more common than myeloid leukemias.6

- Lymphoid leukemia accounts for about 10% of blood cancers in dogs.6

Causes of Leukemia in Dogs

We don’t know the “one cause” of why some dogs develop leukemia.

Exposure to radiation and carcinogens such as benzene and phenylbutazone have been implicated in people. Specific viruses can lead to leukemia in cats, cattle, and birds. However, these causes have not yet been shown in dogs.1

Risk Factors

Leukemia can occur in any breed or age of dog.

Golden Retrievers and German Shepherds are two breeds that possibly have an increased risk of acute leukemia. Acute leukemia may also be more common in male, middle-aged dogs.5

Other breeds that possibly have an increased risk of chronic leukemia: Pit Bulls, English Bulldogs, Boxers, Shih Tzus, Jack Russell Terriers, Dachshunds, and Cocker Spaniels. Chronic leukemia may also be more common in older dogs of either sex.3,7,8

Symptoms

Dogs with acute leukemia are often quite sick. Common symptoms of dogs with acute leukemia include:

- Lethargy

- Decreased appetite

- Weight loss

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

Less common symptoms of acute leukemia in dogs include:6

- Fever

- Labored breathing

- Altered neurological status (cognitive problems)

- Increased thirst and urination

If your dog with leukemia didn’t have any of these symptoms, that’s quite common. Many dogs with chronic leukemia do not have any symptoms at the time of diagnosis. Their veterinarian usually finds it in routine wellness blood screening.

When a dog with chronic leukemia does feel sick, the symptoms are usually vague and non-specific. These symptoms include:6

- Lethargy

- Reduced appetite

- Intermittent vomiting

- Increased thirst and urination

Some dogs may have swollen or prominent lymph nodes (this can happen with either acute or chronic leukemia). However, if lymph nodes are enlarged, they are typically not as enlarged as in dogs with lymphoma.6,9

Diagnosis of Canine Leukemia Can Be Tricky

Leukemia can have similar physical exam and blood work findings as other diseases, including lymphoma and the tick-borne disease Ehrlichia. This means leukemia is sometimes misdiagnosed at first. More tests specific to leukemia are needed to avoid misdiagnosis of canine leukemia.

Correctly identifying the type of leukemia helps determine prognosis and treatment plans.

Your dog’s veterinarian or veterinary oncologist may recommend some or all of these tests:

- Bloodwork, especially the Complete Blood Count — a standard blood panel that looks at red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets.

- A normal lymphocyte count is less than 3,500 cells per microliter. This count may range from 6,000 to over 100,000 cells per microliter in dogs with lymphocytic leukemia.5

- Dogs with myeloid leukemia may have a normal white blood cell count.5

- Blood Smears. This test involves gently wiping a drop of your dog’s blood across a slide, so that the veterinary pathologist can look at the individual blood cells on a microscope. This veterinary specialist can evaluate the maturity of the blood cells, screen for signs of malignancy, and look for abnormal cell numbers.5

- Immunophenotyping. This process uses antibodies to identify the type of cell in a sample, which helps identify the exact type of leukemia your dog has. Immunophenotyping can be done with a blood sample from your dog’s vein or from a fine needle aspirate.10

- Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR). This test uses DNA to differentiate leukemia from other reasons for an increased lymphocyte count.6

- Bone Marrow Aspirate. This test involves using a very large needle to get a sample of the bone marrow to submit for testing and evaluation. It is invasive and painful and is generally only done if other tests have not yielded a diagnosis.6

- Imaging. Radiographs (x-rays) and/or abdominal ultrasound may be done to check the lymph nodes, lungs, and other organs for evidence of disease.8

Prognosis and Staging

Staging is the process of determining the extent of cancer in the body. It can help determine treatment plans and refine your dog’s prognosis. There is no true, well-developed clinical staging system for lymphoid leukemia in dogs. We hope that one is developed in the future.

For now, the following guidelines may help you orient yourself:

The Prognosis for Acute Leukemias

Acute leukemias are more aggressive, infiltrative, and have a rapid disease course. The reported survival time in dogs is days to months (1-120 days).10,11

Dogs with a normal red blood cell count and normal neutrophil (white blood cell that helps fight off infection) count at time of diagnosis had a better overall prognosis and increased survival time.11

The Prognosis for Chronic Leukemias

For chronic leukemias there is wide variability in reported survival times.

With successful treatment, some dogs can survive years with chronic leukemia.

Without treatment, survival times depend on whether your dog had symptoms and how abnormal his bloodwork was at the time of diagnosis.

Treatment

Let’s get the bad news out of the way: in general, leukemia in dogs cannot be cured, but it can be managed with a focus on life quality.

For example, dogs with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) usually don’t go into remission. However, they can live with chronic leukemia for a long time – years in some cases. That said, even mild cases that respond well to treatment still progress, ever so slowly. Eventually, leukemia usually wins.

Dogs with acute leukemia usually have rapidly progressing disease, no matter what treatment they are given.

Even so, dogs with either acute or chronic leukemia who are showing symptoms of illness can be helped with supportive therapy. These kinds of treatments include:6

- broad-spectrum antibiotics to prevent sepsis (an infection in the bloodstream)

- intravenous fluids to correct dehydration

- nutritional support

- blood transfusions

So what other treatments might your veterinarian suggest? Because leukemia is systemic — it is everywhere — the most promising is chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy

There is much to learn about the successful treatment of acute leukemia in dogs. There are not a lot of dogs that get it, the disease is very aggressive, and the dogs who get it are typically very sick when diagnosed,11 so few veterinary oncologists have experience treating it.

But we do know aggressive chemotherapy is typically needed.

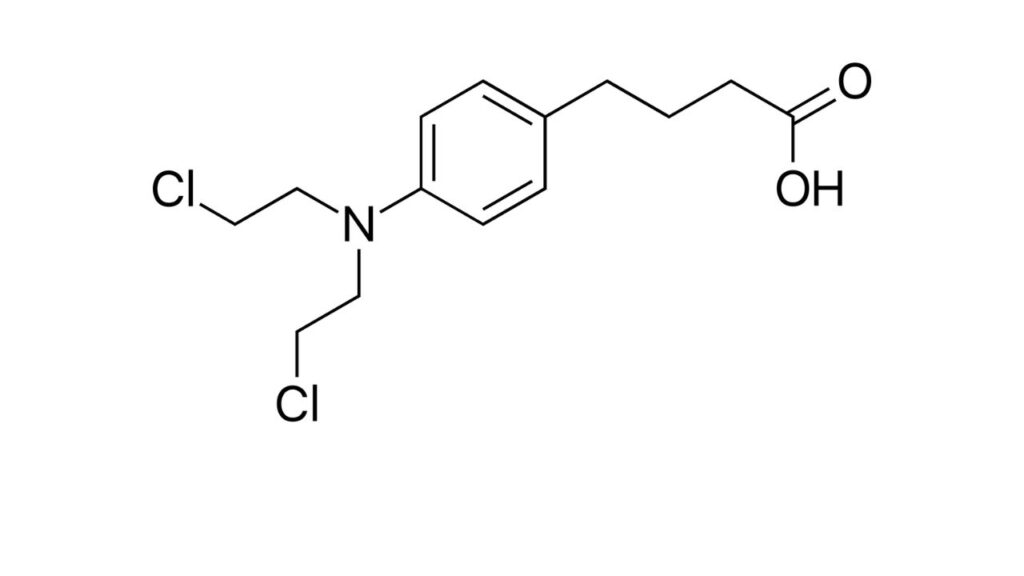

Chemotherapy agents that have been used for acute leukemias include:

- Vincristine

- Prednisone

- Cytosine arabinoside

- Cyclophosphamide

- L-asparaginase11

- Prednisone-based multi-drug chemotherapy protocols such as CHOP, typically used in lymphoma13

- Doxorubicin, usually as a rescue agent for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL)6

Cytosine arabinoside in combination with an anthracycline leads to long-term overall survival in humans with acute leukemias. This approach may be promising for dogs with acute leukemia.11

First-line treatment options typically used for chronic leukemias include:

- Corticosteroids such as prednisone

- Chlorambucil

- Cyclophosphamide

- L-asparaginase

Additional chemotherapeutic drugs may be considered if a dog is poorly responsive to first-line therapy, or if ‘malignant transformation’ (sudden increase in progression) occurs.

Boxers generally have a poor prognosis. For other dogs, treatment with corticosteroids and chlorambucil often provided longer survival times.8

Chemotherapy rarely results in tumor lysis syndrome, a very serious and life-threatening complication. Tumor lysis syndrome occurs when a large number of cancer cells die and flood the body with debris. If it happens, it is usually during the very first chemotherapy appointment. Symptoms include vomiting, diarrhea, and lethargy, and death can occur within hours after chemotherapy is started. Hospitalization and aggressive intravenous fluids are needed to save dogs with tumor lysis syndrome.6 The veterinarian or oncologist will carefully monitor your dog during and after administering chemotherapy, especially on the first visit, to ensure they are well before discharging them.

Radiation

Radiation to the whole body is a part of leukemia treatment in certain specific situations:

- As part of the procedure for a bone marrow or peripheral blood stem cell transplant14

- When leukemia has spread to the brain and spinal fluid or the testicles

- To relieve severe bone pain15

Dr. Steven Suter pioneered bone marrow transplants for dogs. Is it right for your dog? Listen in on DOG CANCER ANSWERS.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a promising option for treating leukemia in dogs. However, most treatments are still considered experimental.

Stem cell transplants potentially cure various blood diseases (including blood cell cancer) in people. Unfortunately, a cure — even with aggressive transplantation — is not anticipated in dogs.9,16,17

One promising therapy uses Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) cells specially engineered to target and kill cancer cells. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cells targeting the CD19 receptor on leukemia and lymphoma cells have been quite helpful in humans. The FDA has even approved the first treatment of this type for CD19-positive Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) in humans. We don’t (yet) know if the same tumor-associated antigens are usable targets in canine leukemia.18

Dogs represent a good model for cancer immunotherapy research in humans.19 This suggests there will continue to be studies in both species, hopefully leading to more treatment options in the future.

Surgery

Surgery is not considered a treatment for chronic or acute canine leukemia. Unfortunately, cancerous leukemia cells are spread widely throughout the bone marrow and blood. There is no one tumor site to cut out: they are everywhere. That’s why surgery is not a cure.12

Vaccine

Vaccines to treat acute leukemia in humans are currently being tested. There are no vaccines available to dogs at this time.20

Diet

There are no specific dietary recommendations for dogs with leukemia, but general dietary advice might be considered.

Supplements

Several supplements have been studied in vitro (tested outside of a living body) in blood cell cancer lines.

- Quercetin has been examined in blood cancers21 and its use has been reported in conjunction with chemotherapy in Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL).22

- Beta glucans has shown promise in patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML).23

- Curcumin is generally considered to have anticancer, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, immune system, and liver protectant properties.24

- Moringa oleifera extracts have been suggested to have anti-leukemic effects.25

Integrative Therapies

Although there is generally a lack of “hard” evidence for integrative therapies, a study showed that traditional Chinese medicine may be helpful when combined with conventional Western medicine to treat patients with leukemia. Together they may positively impact survival in these patients.26

The Final Stages of Leukemia in Dogs

The prognosis for dogs with acute leukemia is poor, and many dogs are very sick at diagnosis. For these reasons, many owners consider euthanasia early in the process. Once a dog reaches the final stages of acute leukemia, symptoms are severe and include respiratory problems, fever, and systemic infections (sepsis).10,28

On the other hand, dogs with chronic leukemia can survive for months to years with the disease, often with good life quality. They will eventually start to feel very sick as the disease progresses.

One possible final stage in canine chronic leukemia is the development of large cell lymphoma (cancer of the lymph nodes, called Richter’s syndrome in humans).6 Many dogs are euthanized when they feel so sick that it affects their quality of life.

Prevention Strategies

There is no known way to prevent leukemia in dogs. Prevention of leukemia in people may be possible by avoiding exposure to certain risk factors such as smoking, benzene exposure, and high-dose ionizing radiation.29

Dr. Douglas Thamm explains how Tanovea, a medicine developed for lymphoma, might be used in other blood cancers on DOG CANCER ANSWERS.

- Brooks W. Lymphocytic Leukemia in Dogs. Veterinary Information Network . https://veterinarypartner.vin.com/default.aspx?pid=19239&id=4952613. Published April 20, 2022. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Rishniw M. Canine Leukemias. Veterinary Information Network. https://www.vin.com/members/cms/project/defaultadv1.aspx?pid=11200&id=6331594&f5=1. Published July 6, 2017. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Avery AC. The genetic and molecular basis for canine models of human leukemia and lymphoma. Frontiers in Oncology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2020.00023/full. Published January 24, 2020. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Miglio A, Antognoni MT, Miniscalco B, et al. Acute undifferentiated leukaemia in a dog. Australian Veterinary Journal. 2014;92(12):499-503. doi:10.1111/avj.12273

- Novacco M, Comazzi S, Marconato L, et al. Prognostic factors in canine acute leukaemias: a retrospective study. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. 2015;14(4):409-416. doi:10.1111/vco.12136

- Presley RH, Mackin A, Vernau W. Lymphoid Leukemia in Dogs. Vetfolio. http://vetfolio-vetstreet.s3.amazonaws.com/mmah/65/86d78e03634afbbc90bc1ac382c568/filePV_28_12_831.pdf. Published December 2006. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Bromberek JL, Rout ED, Agnew MR, Yoshimoto J, Morley PS, Avery AC. Breed distribution and clinical characteristics of B cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia in dogs. Wiley Online Library. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/jvim.13814. Published January 6, 2016. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Rout ED, Labadie JD, Yoshimoto JA, Avery PR, Curran KM, Avery AC. Clinical outcome and prognostic factors in dogs with B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: A retrospective study. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1111/jvim.16160. Published April 30, 2021. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Suter SE, Hamilton MJ, Sullivan EW, Venkataraman GM. Allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation in a dog with acute large granular lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 2015;246(9):994-997. doi:10.2460/javma.246.9.994

- Adam F, Villiers E, Watson S, Coyne K, Blackwood L. Clinical pathological and epidemiological assessment of morphologically and immunologically confirmed Canine Leukaemia. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. 2009;7(3):181-195. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5829.2009.00189.x

- Novacco M, Comazzi S, Marconato L, et al. Prognostic factors in Canine acute leukaemias: A retrospective study. Veterinary and Comparative Oncology. 2015;14(4):409-416. doi:10.1111/vco.12136

- Acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) in adults. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia.html. Published October 17, 2018. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Comazzi S, Gelain ME, Martini V, et al. Immunophenotype predicts survival time in dogs with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2010;25(1):100-106. doi:10.1111/j.1939-1676.2010.0640.x

- Sandmaier BM, Bethge WA, Wilbur DS, et al. Bismuth 213–labeled anti-cd45 radioimmunoconjugate to condition dogs for nonmyeloablative allogeneic marrow grafts. Blood. 2002;100(1):318-326. doi:10.1182/blood-2001-12-0322

- Radiation therapy for acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL). American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/acute-lymphocytic-leukemia/treating/radiation-therapy.html. Published October 17, 2018. Accessed December 11, 2022.

- Graves SS, Parker MH, Storb R. Animal models for preclinical development of allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. ILAR Journal. 2018;59(3):263-275. doi:10.1093/ilar/ily006

- Loke J, Buka R, Craddock C. Allogeneic stem cell transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: Who, when, and how? Frontiers. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2021.659595/full. Published March 23, 2021. Accessed November 30, 2022.

- Klingemann H. Immunotherapy for dogs: Running behind humans. Frontiers in Immunology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2018.00133/full. Published January 16, 2018. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- Dow S. A role for dogs in advancing cancer immunotherapy research. Frontiers in Immunology. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fimmu.2019.02935/full. Published November 29, 2019. Accessed December 1, 2022.

- Barbullushi K, Rampi N, Serpenti F, et al. Vaccination therapy for acute myeloid leukemia: Where do we stand? Cancers. 2022;14(12):2994. doi:10.3390/cancers14122994

- Maso V, Calgarotto AK, Franchi GC, et al. Multitarget effects of quercetin in leukemia. Cancer Prevention Research. 2014;7(12):1240-1250. doi:10.1158/1940-6207.capr-13-0383

- Spagnuolo C, Russo M, Bilotto S, Tedesco I, Laratta B, Russo GL. Dietary polyphenols in cancer prevention: The example of the flavonoid quercetin in leukemia. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1259(1):95-103. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06599.x

- McCormack E, Skavland J, Mujić M, Bruserud Ø, Gjertsen BT. Lentinan: Hematopoietic, immunological, and efficacy studies in a syngeneic model of acute myeloid leukemia. Nutrition and Cancer. 2010;62(5):574-583. doi:10.1080/01635580903532416

- Kouhpeikar H, Butler AE, Bamian F, Barreto GE, Majeed M, Sahebkar A. Curcumin as a therapeutic agent in leukemia. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2019;234(8):12404-12414. doi:10.1002/jcp.28072

- Akanni EO, Adedeji AL, Adedosu OT, Olaniran OI, Oloke JK. Chemopreventive and anti-leukemic effects of ethanol extracts of moringa oleifera leaves on wistar rats bearing benzene induced leukemia. Current Pharmaceutical Biotechnology. 2014;15(6):563-568. doi:10.2174/1389201015666140717090755

- Wang Y-J, Liao C-C, Chen H-J, Hsieh C-L, Li T-C. The effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine in treating patients with leukemia. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016:1-12. doi:10.1155/2016/8394850

- Kudo T, Kato Y, Masuno H, Honjo H, Kitazawa K. The effect of repeated acupuncture stimulation on canine lymphocyte response. The Japanese Journal of Veterinary Science. 1987;49(6):1009-1013. doi:10.1292/jvms1939.49.1009

- Ferrari A, Cozzi M, Aresu L, Martini V. Tumor staging in a beagle dog with concomitant large B-cell lymphoma and T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation. 2021;33(4):792-796. doi:10.1177/10406387211011024

- Ilhan G, Karakus S, Andic N. Risk factors and primary prevention of Acute Leukemia. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. http://journal.waocp.org/article_24517.html. Published April 1, 2006. Accessed December 11, 2022.

- CLL staging. Leukemia and Lymphoma Society. https://www.lls.org/leukemia/chronic-lymphocytic-leukemia/diagnosis/cll-staging. Accessed January 30, 2023.

Topics

Did You Find This Helpful? Share It with Your Pack!

Use the buttons to share what you learned on social media, download a PDF, print this out, or email it to your veterinarian.