Scientific evidence is the bedrock of progress. Scientific ideas are only valid if they can be tested, and testing involves accumulation and evaluation of evidence. The one thing that all scientists in all fields follow, trust, and use in their decision-making process is scientific evidence. In this article we will go through how scientific studies are done, how this information can be used by professionals, provide some examples, and share some tricks on how to measure how legitimate a source is.

Key Takeaways

- Evaluating in the scientific process is objectively thinking about how the experiment was designed for testing, how it was accomplished, and what future improvements could be made, if any, to ensure the results are true and valid.

- You can evaluate scientific evidence by following the CRAAP rule: Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose.

- Next, actually read through the study.

- The third step is to interpret if it is a good study, whether we should rely on it (or if we do, under what circumstances), and how useful the data presented can be.

The Importance of Scientific Evidence

In the modern age of technological and medical advancement, scientific evidence is at the center. It is the bedrock of progress. Scientific ideas are only valid if they can be tested, and testing involves accumulation and evaluation of evidence.

In much the same way we were asked to show our work in math class, all advancements in technology and science/medicine need to be proven with evidence that is conducted through tests and evaluations.

The one thing that all scientists in all fields follow, trust, and use in their decision-making process is scientific evidence. The acceptance or rejection of science largely depends on the evidence relevant to it.

This is critically important because most of our major decisions – from how we track the weather, to public health initiates, to medical care for our pets – come from scientific studies and the evidence they provide.

Below, we will walk through a variety of definitions about how scientific studies are done, how this information can be used by professionals, provide some examples, and share some tricks on how to measure how legitimate a source is.

How to Tell If a Research Study Is Worth Reading: the CRAAP Rule

After a vet visit, it’s common for you to want to research both the diagnosis and solutions discussed. We are lucky to have access to infinite information via the internet.

Unfortunately, not all sources are reliable. So how do science professionals determine if a source is reliable?

Before reading deeply into an article, we follow the CRAAP (Currency, Relevance, Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose) rule:1

- Currency: Is the work up to date? The general rule is to rely most on works that were written less than 10 years ago. Of course, there are exceptions to this, but most newer works will reference older papers while also providing more recent findings and advancements.

- Relevance: Is the publication/source of information relevant to the topic being studied or researched? An example would be if you did a search for dog cancer and found a bunch of papers on dog melanoma (skin cancer), but you were looking for information on dog hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer) – while informational, the melanoma articles will not give you the specific information you are looking for.

- Authority: Who is writing the study? Are the author(s) considered reputable in their field? Is the publication/publisher reputable in the scientific community/field of expertise? Publications often have several authors, and while not all will be an expert in the topic the study is focused on, at least one of them should be (usually the primary author).

- Accuracy: Is the study supported by well-defined evidence? Are there appropriate citations to other relevant works to bolster claims? Do they share their sources of information and are those sources considered legitimate utilizing the CRAAP rule?

- Purpose: What is the motivation behind this study? Are there interested parties or financial connections to the publication?

Reading Different Types of Research Studies

Once we have determined that a study is legitimate and trustworthy, it is time to read it and acquire the information it provides.

It is helpful to understand the different types of studies that exist, and while one approach isn’t better than another, this can also help to understand when they are used and how the information contained in a study is relevant to your search.

Research studies include observing and studying the processes that are involved in health, disease, and treatments. These types of studies can involve researching new ways to monitor, prevent, diagnose, and/or treat a disease or health condition.

Research studies generally fall into two main categories, quantitative or qualitative studies.2

- Quantitative studies involve data with numerical values. This can include data that measures sample size or how often something is measured.

- Qualitative studies involve reporting on non-numerical data or variables that can be organized into categories. Examples of this include demographic data such as ethnicity, location, and profession.

Whether a study is qualitative or quantitative, it usually falls into one of four primary types of research studies conducted and published.3

Systemic Review

These works are probably the best types of articles to read through first when trying to understand a new complicated topic.

Also termed a literature review, this type of publication compiles and analyzes all the most relevant literature on a topic. It usually will compile works that can span about a decade giving a snapshot of the most relevant publications in the field on a specific topic to the present day.

Reviews are often written about a broad topic, such as canine mast cell tumors or canine distemper, and are quality reference articles.

Original Research Articles

These are original research studies that are published in peer-reviewed publications about a very specific topic.

An example would be a lab study that determined the best way to diagnose canine distemper. The specific findings from this study would be new original data collected and published in a scientific journal.

Clinical Trials

A type of study that is done to determine new ways to detect, treat, or inhibit disease while also evaluating effectiveness and safety. These can be new drugs, surgical advances and devices, or repurposing use of a drug or treatment from its existing use.

These types of studies can also look at aspects of care such as improving quality of life with respect to chronic illnesses.

Within clinical trials you can have randomized control trials, which are trials that randomly assign participants into different groups for evaluation.

Meta-Analysis

A type of study that reviews previously published data and provides a quantitative and often numerical analysis about the topic. An example of this would be a study looking at incidence of canine parvovirus infection based on geographic location.

Discernment: Is This a Good Study, or Not?

As we’ve said above, the first two steps when doing research are determining if the study is legitimate using CRAAP and then actually reading through the study.

The third step is to discern if it’s a good study or not by determining the following:

- Can we rely on it?

- Under what circumstances?

- How useful is the data presented?

With all of this in mind we can start to interpret the evidence within the study. This can be done using the following criteria for both qualitative and quantitative studies.4

Quantitative Criteria: The Numbers

There are certain things that can be measured directly. We look for quantitative (number) information like:

- Internal validity: Every study is measuring something. Internal validity is when the observed effects of the study were due to the independent variable being measured, not other variables in the study, errors, or some outside factor. In other words, are we sure we know what caused what was observed?

- External validity: The results of a good study can be applied to other contexts. Can the results from the research sample be applied to the general population or “the real world” or would these results only have happened in the controlled circumstances of the study?

- Reliability: Can this study be replicated? Have others in the field published similar or adjacent works that validate parts of this study? Was this study based on previous research and known facts?

- Objectivity: Everyone has biases based on their own lived experience and worldview. Has the personal bias of the authors been removed from the conclusions presented in the study?

Qualitative Criteria: Everything Else

Numbers are important, but they aren’t the only thing when it comes to interpreting a study’s evidence. We look for qualitative (non-numerical) information like:

- Credibility: Are the authors reputable and trustworthy? Most important, are they considered reputable and trusted by their colleagues, by other professionals in the same field? Someone who appears on television or has a YouTube channel might be credible if they are well-respected by their peers as well. But if their only claim to fame is being famous, that does not mean they are credible. Just like a plumber’s work is best judged by plumbers, a scientist’s work is best judged by other scientists who know their field.

- Transferability: Can the findings of this study be applied to a different setting?

- Dependability: Are findings consistent regarding the specific parameters in which the findings were generated?

- Confirmability: Are the conclusions based on the study’s participants and the setting of the study rather than the opinions of the authors?

Peer Reviewed Papers

One of the most common types of studies is a peer-reviewed study published in a scientific publication. During your search, there is a good chance you will come across a few.

These types of studies are written in article form and have gone through a stringent evaluation process where the journal editors and outside expert scholars critically review and assess the quality of a scientific study and merit of the article.5

A manuscript is usually composed of the following components:

- Abstract, or a summary of article

- Headings for organization

- Published methodology (how the study was conducted)

- Citations throughout (references)

- Credentialed authors – these authors are usually affiliated with a research institute or university

If an article passes all the requirements of a publisher, it will be published in that peer-reviewed journal.

These articles are accessible through academic databases, the most common of which are Science Direct, Google Scholar, and Medline (PubMed). These search engines will output studies on the topic of interest, however sometimes studies are only accessible after payment to the publisher.

Each publisher has their own determination for which articles are free access, are behind paywalls, and/or are available through university access, so this is something to be aware of as you are utilizing these search engines.

The publication process involves several steps to assess the validity and merit of a study.

- The work is done, research is concluded, evidence collected, and paper is written.

- The author submits their study/article to journal editor of publication.

- Editors will convene and forward the article to experts in the field of article topic for anonymous impartial review of the manuscript.

a. This process checks for accuracy and validity of research methodology and procedures and conclusions.

b. Reviewers can suggest revisions – particularly if the study lacks rigor or needs further studies to validate a claim/conclusion.

c. The article can be rejected if not enough evidence is present within the article.

This stringent process ensures that the quality and validity of research is at the highest standard when published.

Publications are typically on highly detailed subject matter and involve complex analysis, but often include clinical trial studies and systematic reviews that give a more holistic view of the subject matter.

One limitation of these types of articles is that they are usually highly technical and filled with jargon and can be hard to understand/interpret if you are not a medical professional.

White Papers

Another popular type of publication is the white paper. This type of document was originally used in government reporting to provide quality summarized information to officials for decision making.6

These types of papers provide a succinct overview using well-researched information on what are generally complex topics, allowing the reader to have a more in-depth understanding in a shorter time frame.

White papers are particularly beneficial when trying to understand a topic that you are unfamiliar with from one reliable source.

While very beneficial, it is important to be aware that white papers derived from proven scientific studies can be difficult to distinguish from ‘marketing’ white papers that may only present data to support one perspective.

This style is typically used by groups to argue a particular position or offer a resolution to a problem for an audience that is outside their organization. The presented information can be a sales pitch to sell information or new products as solutions for potential customers. This can be potentially problematic, as the information being presented is not unbiased, and therefore might not provide a comprehensive summary of the topic being researched.

It is important when reviewing white papers to use the CRAAP method discussed above, checking on the sources used to make sure it is reliable.

Historical Use as Scientific Evidence

There is a long history of utilizing scientific evidence. The first scientific journal was published by the Royal Society of Long in 1665.7 However, the rigorous vetting of said evidence is a relatively “new” concept.

In the 17th-19th century, the scientific community consisted of a small select group of people who would regularly communicate and share their findings through personal letters, presentations, and full-length books. A good example of this is On the Origin of Species, by C. Darwin.

Over time this changed to journal editors selecting works that would be published based off the works of members associated with the journal or what they found interesting. As one would suspect, this created a system where dissemination of information was in the hands of a powerful few, which does not lend to objectivity.

Therefore, as scientific expertise expanded in the 20th century, journal editors started to make more informed decisions about what they published and started to form the model for peer-review that is used today.

Real-World Observations

The term “historical use” can also refer to the known and long standing “historical” use of a drug or treatment. This encompasses the original studies and outcomes of said treatment, but also how it has practically been used to treat patients in real world scenarios.

An example of this is the widely used drug Humira. Historically Humira (scientifically known as adalimumab) was developed to treat only one condition, Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). It is now approved to treat plaque psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, Crohn’s disease, psoriasis, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ulcerative colitis, hidradenitis suppurativa, and certain types of uveitis.8

Studies on Humira began in late 1993 and went through rigorous lab testing and then clinical trials until its approval by the FDA in 2002 for use in RA. After about 20 years on the market,9 it has been prescribed more than 2 million times for the variety of conditions listed above.

The versatility and application of this one drug to many diseases is largely due to physicians’ observations of how this drug works in patients with follow up clinical trial studies being done based off historical use evidence.

Historical use is vital because even though clinical trials give us important safety and efficacy parameters to approve treatments, employing these treatments on the public population allows us to see how the treatment works on many patients.

This is significant because many patients (humans and dogs alike) are not only suffering from one ailment, and often have co-morbidities or several chronic ailments. Over time it may turn out that a treatment is also beneficial for a completely different disease.

Clinical trials are not equipped to study so many different variables in one setting. It is important to consider not only how a treatment will affect the specific condition it was designed for, but how it will work alongside treatment of these other ailments. This could lead to observations of this drug working well to treat another disease or its possible adverse effects when taken with another treatment.

These observations fall under “historical use” and are often shared among physicians/vets who practice, but not initially documented in the same fashion as clinical trial data or peer-reviewed research.

Historical use has advantages because it allows for real-world practice and common knowledge to be used in the treatment of a patient. However as historical use is not always followed by additional rigorous scientific studies to support the observations seen in clinics, sometimes it can fall into the box of anecdotal evidence.

Anecdotal Evidence

Anecdotal evidence is usually based on the experiences or observations of an individual. This is separate from evidence that is used to estimate how likely something will be based on the experiences of many individuals (such as survey data).

“Anecdotes are useful for documenting an outcome that can occur but does not give any additional information about if it will occur and at what rate, or if an intervention can change the incidence of occurrence.” – David Eddy10

Anecdotes alone can have limited use in judging the effectiveness of health interventions. To determine what kind of treatments work in a disease group, the opinion or observations of one person are not reliable.

- This is often because anecdotes are given when the outcome is positive, and patients or doctors want to share good news. This type of evidence can sometimes be seen as an individual’s interpretation and should not be the sole evidence relied upon.

- Rarely are negative anecdotes recorded, as those that don’t receive the benefit of an intervention or have a negative reaction are silent.

The stories you may see shared in social media forums, or the reviews on ecommerce sites, are good examples of anecdotal evidence. They may be accurate reflections of an individual outcome, but they are not proof that the same outcome will occur in another case.

That said, anecdotes can be helpful in certain situations. When enough anecdotal evidence accumulates, particularly in the clinical setting among practicing physicians, this can trigger a more thorough study of the evidence potentially leading to clinical reporting.

In fact, most scientific and medical discoveries start with an anecdote, which is followed by meticulous testing and the scientific method. When reading studies, you may notice the introduction utilizes an anecdote to point to why a more thorough examination of this topic is now being researched.

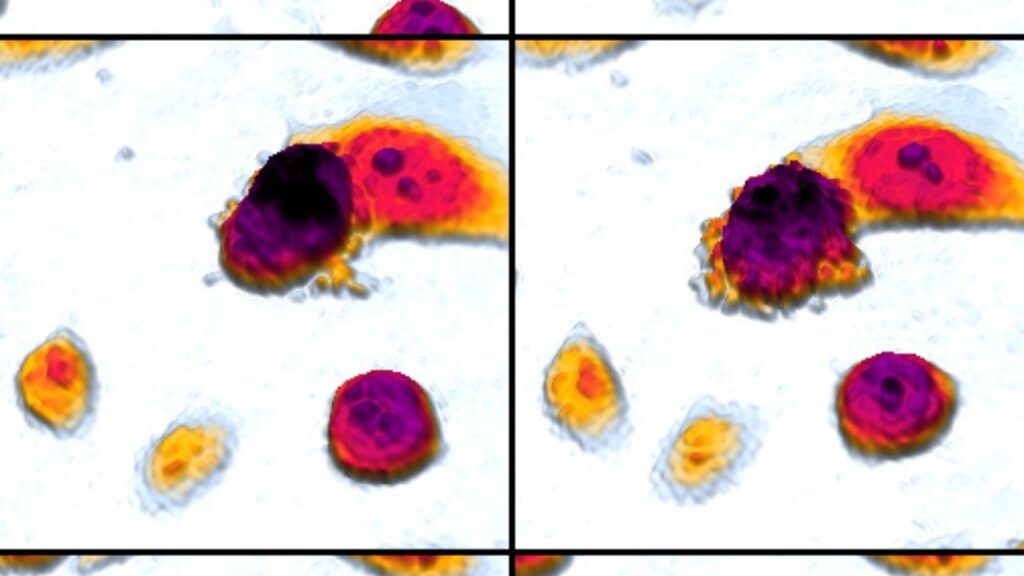

Biological Evidence

Biological evidence is most famously known for its use in forensic science but is also regularly used for diagnosing diseases and creating a treatment plan. This evidence comes from a living organism and can include hair, tissue, bones, teeth, and blood.

It is commonly analyzed in the following ways:11

- Toxicology: Detection and identification of toxic substances that may be present in the sample. This can be useful when trying to detect if your dog ingested something potentially poisonous.

- DNA analysis: Allows for study of the genetic code of the sample. This information can be used for genetic testing that can provide information on hereditary issues and/or cancer.

- Histopathology: This is an examination of tissue samples under a microscope to assess shape, size, color, and other measures that could indicate an abnormality such as an infection or cancer.

This type of evidence, when collected and tested properly, is the most concrete form of evidence, particularly when compared to symptomatic or anecdotal evidence. The limitations to this type of evidence are that it must be handled properly as biological material is prone to contamination and degradation.

The correct type of sample must be collected and subject to the right test to produce truthful scientifically correct answers. For example, natural compounds like peroxides can mimic positive results for biological tests and must be taken into consideration.

Additionally biological evidence can have a time limit or feasibility window before it is no longer a useful piece of information.

Watch for Red Flags

When evaluating scientific evidence, make sure you are aware of the following things to determine if the claims are valid/true:12,13

- Are the methods clearly published? Credible science describes how the study was done and what observations were found. If the methods are not included, this is a huge red flag.

- The type of evidence provided is mostly anecdotal. If all the claims are only testimonials and anecdotal stories, this is a cause for concern. As mentioned above, anecdotal evidence has its merits but is not the only type of evidence and certainly not the best to support scientific claims.

- If there is not an identifiable publisher (credible news source, scientific publication, etc.) the information should not be relied upon, unless backed by other sources that meet the criteria for credibility.

- Purpose for providing information: Is the evidence given as part of a sales pitch? Is there a conflict of interest? Does the source seem neutral? If a source does not seem neutral, this is a red flag.

- Date of publication: Make sure that the evidence that is being used is up to date and current in the field. If a source is using evidence that was published a decade ago with no comment on newer investigations in that field, it could be a red flag.

There is an abundance of useful information available at our fingertips. When doing your own research, particularly about your beloved dog, remember to always confirm your key findings with your veterinarian. They know the whole picture of your dog’s health, and can see how your new information might fit into a current treatment plan. They are the ones who have cared for and know your individual case best.

- George, T. (2022, December 7). Working with Sources. Retrieved from Scribbr: https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/credible-sources/

- Statistical Language. (n.d.). Retrieved from Australian Bureau of Statistics: https://www.abs.gov.au/websitedbs/D3310114.nsf/Home/Statistical+Language+-+quantitative+and+qualitative+data#:~:text=Quantitative%20data%20are%20data%20about,variables%20(e.g.%20what%20type).

- College, S. L. (2012, April 2). Evaluating Information. Retrieved from Sarah Lawrence Library Guide: https://sarahlawrence.libguides.com/c.php?g=611833&p=4248617

- Frambach, J. M., van der Vleuten, C. P., & Durning, S. J. (2013, December 7). Quality Criteria in Qualitative and Quantitative Research. Academic Medicine, 552. Retrieved from Scribbr: https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/institute_excellence_education/pdf/Quality_Criteria_in_research.pdf

- Finding and Using Health Statistics- Peer Reviewed Literature. (n.d.). Retrieved from National Library of Medicine: https://www.nlm.nih.gov/nichsr/stats_tutorial/section3/mod6_peer.html#:~:text=Peer%2Dreviewed%20journal%20articles%20have,in%20the%20peer%2Dreviewed%20literature.

- University, P. (n.d.). Purdue Online Writing Lab. Retrieved from White Paper: Purpose and Audience: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/professional_technical_writing/white_papers/index.html

- Hosking, R. (n.d.). Broad Institute. Retrieved from Peer Review- A Historical Perspective: https://mitcommlab.mit.edu/broad/commkit/peer-review-a-historical-perspective/

- Judith Stewart, B. (2022, Aug 25). Drugs.com. Retrieved from Humira FDA Approval History: https://www.drugs.com/history/humira.html

- Quality, A. f. (2022, August). ClinCalc.com. Retrieved from Adalimumab: https://clincalc.com/DrugStats/Drugs/Adalimumab

- Irwig, L., Irwig, J., & Trevena, L. (2008). Smart Health Choices: Making Sense of Health Advice. London: Hammersmith Press. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK63643/#:~:text=Anecdotal%20evidence%20is%20usually%20based,with%20large%20numbers%20of%20people.

- Coyle, H. M. (2012). The importance of scientific evaluation of biological evidence – Data from eight years of case review. Science & Justice, 268-270

- Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2017, May 5). Read at Your Own Risk: Three Red Flag to Look for When Evaluating On-line Articles. Retrieved from HuffPost.com: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/read-at-your-own-risk-thr_b_9844468

- Evaluating Health Information. (n.d.). Retrieved from UCSF Health: https://www.ucsfhealth.org/education/evaluating-health-information

Topics

Did You Find This Helpful? Share It with Your Pack!

Use the buttons to share what you learned on social media, download a PDF, print this out, or email it to your veterinarian.